A Stroll Through the Spiritual Landscape of Archaeology

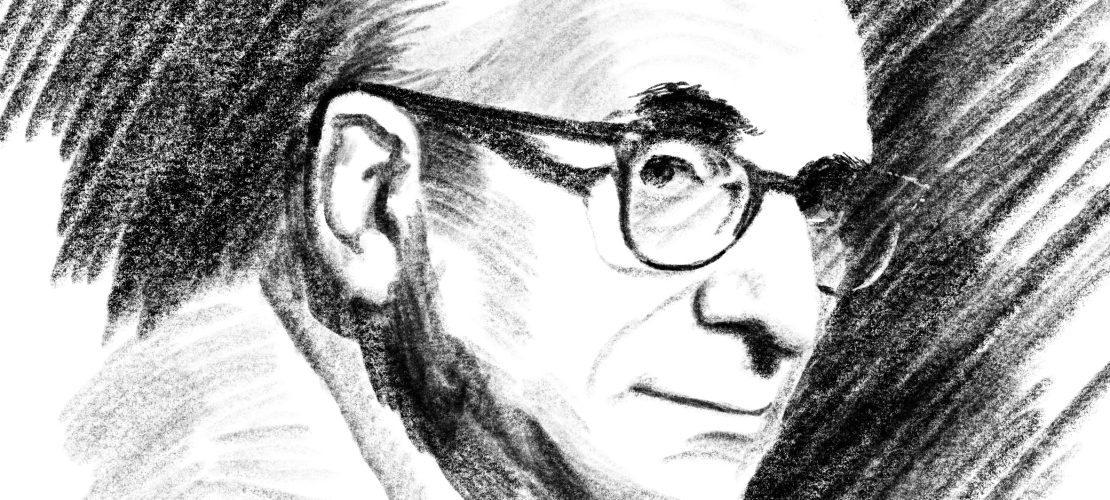

Article: ِAnthropology, Mohammed Abdallah altrhuni

After his return from Brazil, Claude Lévi-Strauss spent most of his time classifying the artifacts he had brought back. In his spare moments, he had begun writing a novel, but he abandoned it after fifty pages. Lévi-Strauss’s excuse for not finishing it was his lack of imagination. All that remained of the novel was its title: Tristes Tropiques (Sad Tropics). For Strauss was incapable of setting his sadness aside; whether crowned by falsehood or cowardice, it always finds its way into your heart and does not leave.

At sixteen, he read Marx without realizing he was awakening sleeping mountains. He studied philosophy without recognizing it as that which exposes sadness. Strauss was an intellectual, and his student years were spent between the two specters of Classicism and Modernity. He was confused and lost his battle with mathematics and the more obscure aspects of the Greek language. He abandoned the dream of the École Normale Supérieure and vanished into the folds of a law school. Because he was faithful to philosophy, not to the Greeks, he continued to study it at the Sorbonne. There, he found his first wife, Dina Dreyfus, like a lone apple tree. They were brought together by socialism, philosophy, and a pure sadness bound by a knot of talent.

During this period, he was a political firebrand on one hand, and on the other, he lived the nightmares of inert law books. Undoubtedly, Strauss’s relationship with the journal Documents was like reaching a place of final sighs: Bataille’s madness, Leiris’s terror, the cries of the special note-taker André Schaeffner. But more important than all of this was the strong friendship that bonded him with the Swiss-French anthropologist Alfred Métraux. Up to that point, Strauss knew nothing about anthropology.

After graduation, he worked as a teacher and had to complete his military service. He experienced financial distress, and the only escape from his thoughts was walking in the hills surrounding Paris. While searching for a profession other than teaching, he found, on the margins of the humanities, a new but sorrowful field of research. Finally, in the 1930s, the door to ethnographic research opened in France. It was Paul Nizan who suggested anthropology to Strauss, as it suited his sadness and introverted nature. What most ignited Strauss’s interest and passion was fieldwork, which combined idea and journey. Anthropology is what gave Strauss the chance to escape Europe. He himself admits that the destination was arbitrary; some even say the choice of anthropology itself was random. The decision was to become a journalist after he was nearly consumed by the teaching profession. He took advice from Marcel Mauss, who told him that Indians in Brazil were still running naked in the forests. In early February 1935, Strauss, accompanied by his wife Dina, was on board the ship Mendoza, en route to there.

Strauss had not planned to become an anthropologist. He even says about his journey and his book:

“I hate travelling and explorers. And here I am, about to tell the story of my expeditions. But how long it has taken me to make up my mind to do so! It is now fifteen years since I left Brazil for the last time and, during all that time, I have often planned to undertake the present work, but on each occasion, a sort of shame and repugnance prevented me from making a start. Why, I asked myself, should I give a detailed account of so many trivial circumstances and insignificant happenings?”

Strauss undertook all those journeys because of sadness, and his anthropological narrative in Tristes Tropiques is but a structure of profound sorrow. Strauss wrote about the details of his discoveries in Brazil, but he also wrote about his mournful journey and how he became an anthropologist. The secret to this book’s success is the sadness that snaps its fingers in his soul every evening. Strauss was sad because he was taking anthropology into the tunnel of philosophy, which questions the conditions and possibilities of human life. And he was sadder still because he wanted his book to be literary, for the French intellectual to read, not the anthropologist. But when he wanted to write about his experience, readers found anthropology in his text. Unknowingly, he had written an interdisciplinary text, possessing a poeticism absent from literary texts.

The sad paradox Strauss came to know was that he would never fully know those societies he studied. This truth makes exploration a sorrowful journey revolving in a tragic void. There is a bitterness in anthropological research due to undefined memory; Strauss did not know if he was searching for the past of a tribe in Brazil or for his own past. Was he exploring the Other, or was he exploring himself, trying to plant his being in the soil of anthropology? There is a feeling the anthropologist has of the end of innocence, and with it, the ancient indigenous societies. This feeling sows sadness due to the sense of the disappearance of what remains of purity in this world. In this sense, Strauss hated the exploration that gave him the chance to see the world in its primal seed.

Strauss’s sadness was greater than others’ because he wrote Tristes Tropiques after losing hope of being an anthropologist:

“I broke with my past, rebuilt my private life, and wrote Tristes Tropiques, which I would never have dared to publish had I been competing for a university post.”

Strauss thought he would not find sadness on the fringes of the Amazon basin—a man walking behind mules, carrying his sadness and a memory containing what the world cannot fathom. But sadness found him, and it turned in his heart into a bitterness whose end is an ecstasy whose source only the anthropologist knows. In Strauss’s anthropology, there is an uncontrollable shudder, a sadness, and a bitter tone that moistens the voice. But Strauss is not alone in feeling this sadness that anthropology understands so well; every anthropologist carries this lean, solid sadness.

Mahfoud Bennoune, the Algerian anthropologist, carried the sadness of anthropology and its harsh spiritual exercise. In response to a question posed to him: “What does it mean to be an anthropologist from the Third World?”

Mahfoud Bennoune says:

“This question requires an answer derived from my personal experience, or at least based on it. As a former farm worker, a migrant laborer, a militant in a national movement, a student of anthropology, and a professional anthropologist, circumstances forced me to abandon a discipline which I still value highly, in spite of the critical observations and serious reservations which I shall voice later concerning its general orientation, its methodological flaws, and its epistemological deficiencies.”

Bennoune was a member of the Algerian People’s Party and a member of the National Liberation Army, and he experienced imprisonment during the colonial era. After Algeria gained independence, he found himself pursued and forced to leave Algeria. In exile, he became convinced that to effect change in his country, a serious study of the social and cultural reality of the society to be changed was necessary. He had begun preparing for a university degree in economics and philosophy, but after reading the works of Leslie White, Barrington Moore, and others, he preferred to study anthropology and social history. For his PhD in anthropology, he specialized in four subjects: the origin of the state, economic anthropology, peasant societies and cultures, and the Middle East and North Africa as his geographical area of specialization.

We note that Bennoune and Strauss meet on many points; both came from poor families, both lived the political experience, and both left their field of study and chose anthropology. Bennoune was fascinated by anthropology: “What discipline could be nobler and more sublime than one that analyzes and compares, in a systematic and extremely precise manner, the characteristics, origins, evolution, and conditions of all peoples, cultures, and societies?”

Mahfoud Bennoune believed that anthropology was a truly revolutionary science, capable of contributing to a desired struggle to eliminate ethnocentrism, chauvinism, and racism, and why not exploitation? But reality was entirely different; Western anthropology is the child of colonialism, and it is directed at studying the Other, namely the Third World. How can an anthropologist from the Third World, from the Other, discover that there is little interest in the specific conditions under which anthropological research was conducted during the colonial period? It is even more astonishing to discover that those anthropologists were the primary beneficiaries of that period, during which their countries dominated other Third World nations. He also discovers that hardly any European or American anthropologist was convinced by the subordinate culture they studied. Bennoune was ordered to study a small group of migrant workers in complete isolation from the colonial historical, social, and economic context. After obtaining his PhD, he taught for two years in America, then returned and joined the faculty at the University of Algiers. He was shocked to learn that anthropology had been abolished on the pretext that it was a colonial science, and he commented on this, saying:

“Since most modern sciences, such as chemistry, physics, engineering, geography, and others, have contributed, directly or indirectly, to the success of European colonialism, you ought to be fair to yourselves and ban them as well.”

In the Third World, the anthropologist Mahfoud Bennoune found himself stuck in an ambiguous and contradictory position, arousing tensions and contradictions that kept him in a continuous intellectual and existential crisis. Strauss was sad because he was an anthropologist during the colonial period, and a socialist revolutionary. Mahfoud Bennoune is sad because he is an anthropologist in the Third World that Strauss studied. The anthropologist is sad because life places him on the thin surface of its emotions; in every journey, the rhythm changes and new rituals appear. What remains, clearly recorded in the anthropologist’s notebook, is his sadness. There is blame, doubt, and a feeling of bewilderment. What hidden miracle does this sad anthropology hold for the Third World? What hidden miracle does anthropology possess other than pale words about the past and indigenous peoples? We must have our own anthropology. It, too, will be sad, but the only consolation in all of this is that the scent of our hands and the color of our skin will be imprinted in its words.

Mohammed Abdallah AlThrhuni

writer and researcher