The Illusion of War in rockart of the Acacus

Article: Shamanism, Mohammed Abdallah altrhuni

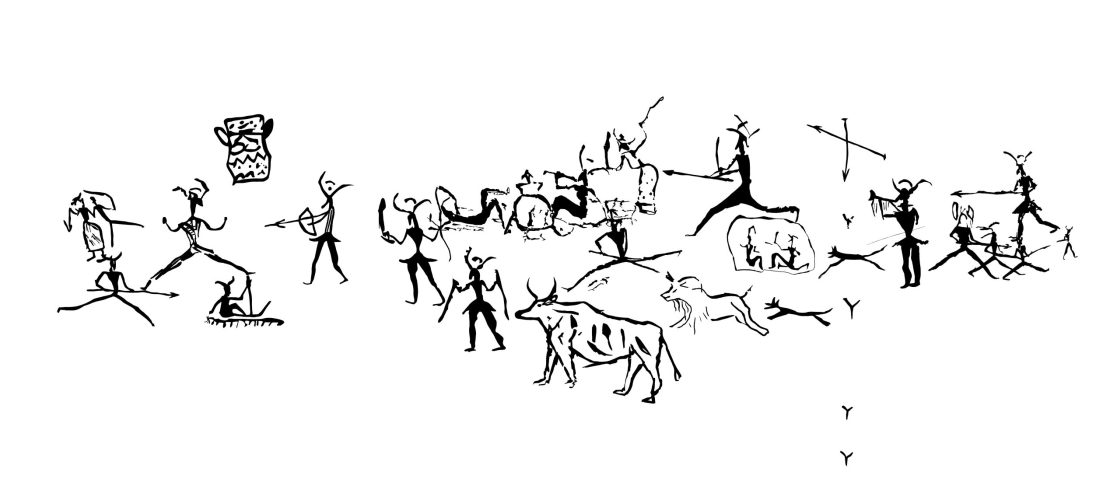

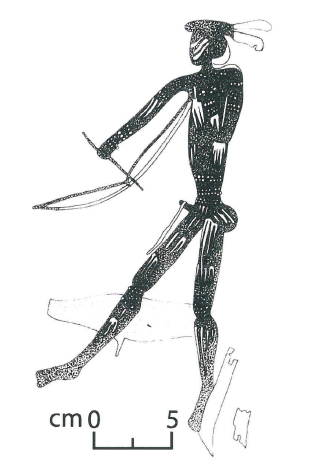

A mural from Wadi Awis in the Acacus presents us with more than we can comprehend. Every observer of the scene senses it opens onto a horizon of war and combat—bows, arrows, spears—and we feel a profound impact due to the bloody scene. For every mural in the Acacus and other rock art sites that shows arrows and spears, we find the usual description: “a combat scene or a hunting scene.” These murals have been interpreted on a realistic basis, describing spears, bows, victors, and vanquished. This applies to many murals of the Horse Period, linked to the appearance of the metal-tipped spear.

However, if we look at this mural (Figure 1) from a shamanic perspective, we may pause at features that cannot be explained on a realistic basis. Let us pause for a moment with the “Medicine Dance of the !Kung Bushmen” to consider the matter from a different angle:

“Gau N!a is the great god of the !Kung people, creator and controller of all things. Gau N!a has a dual nature; he is the giver of life and the giver of death who does not approach humans, yet he constantly intervenes in their lives, sending good and evil according to his will, not according to human merit. Gau N!a has messengers to carry out his orders, and they have some autonomy in their work reflecting the duality of their master. Therefore, the !Kung often plead with them for mercy… During the medicine dance, Gau N!a and his assistants, the Gauwa-si, are usually hidden in the shadows behind the dance circle. Gau has sent them with sickness and death. Fighting the Gauwa-si and the sickness and death they may bring is an integral part of the medicine man’s function. To expel them, the medicine men display an aggression and violence not shown in daily life. They rush towards the shadows, throwing sticks while screaming, cursing, and shouting at the bringers of death to leave and take their evils with them.”

1- Wadi Awis, by shefa salem

As for Lewis-Williams, he says: “The many flying arrows in the mural are probably not real but depict arrows of sickness.” In the poetic interpretation of rock art murals and engravings, metaphor must be taken into account. Despite significant linguistic differences, the modern !Kung language and the extinct Southern !Xam language used the same word to denote both fighting and a dangerous amount of potency. “Thus, it could be interpreted that the mural depicts combat as a metaphor from San language to denote intensely concentrated potency. Another possibility, perhaps better, is that the mural depicts a hallucinatory combat among a group of spiritual healers. Southern San groups acknowledged a category of healers who deliberately shot arrows of sickness at their enemies.”

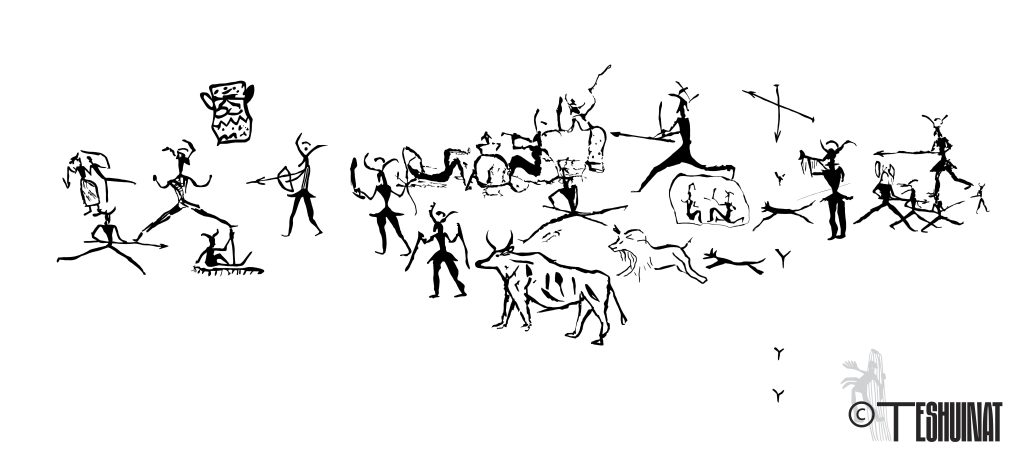

For further understanding, let us look at a mural of the San people in South Africa (Figure 2). Lewis-Williams says that in the mural there is a shelter. Inside this shelter, there is a central figure lying down, wearing a long garment—the only type of garment among the San people. The mural embodies a dance where people raise sticks above their heads. The circle of dancers includes a group of males, and in the outer circle, there are bows, arrows, sticks, and spears. The interpretation of the mural for Lewis-Williams is that it represents a girl’s puberty dance. He himself says there is no evidence that such a dance was actually performed by the !Xam tribe, but this interpretation aligns with what Marshall mentioned about this mural. Williams points out that the girl remains isolated in the menstrual hut around which the Eland Bull Dance is performed. Williams also indicates that the sticks likely represent antelope horns and concludes that the dance is merely a simulation of Eland mating behavior.

2- James David Lewis-Williams

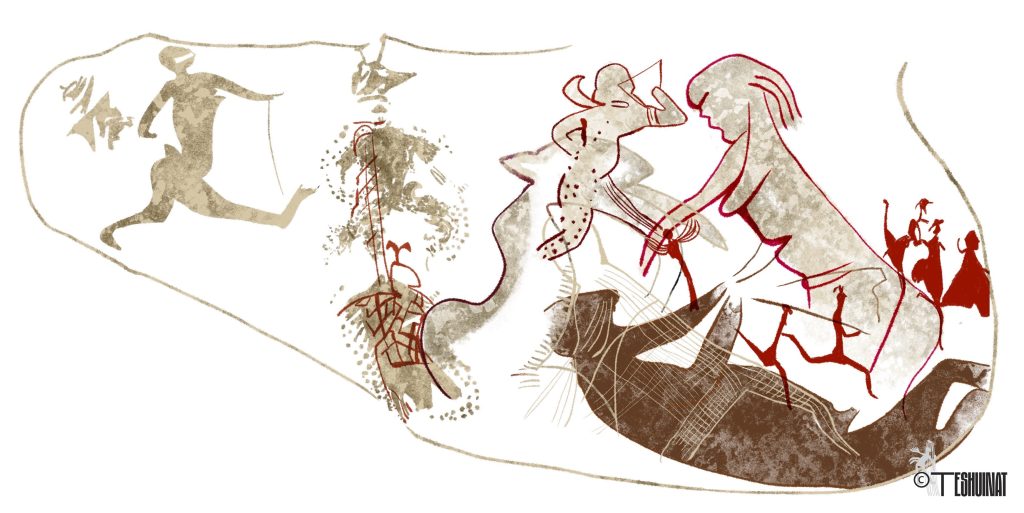

We might have been completely convinced by what Williams said, had we not paused at another San mural, which Lewis-Williams himself discussed in an article titled “The Eland’s Dream: An Unexplored Component of San Shamanism and Rock Art”. The mural (Figure 3) is from the Natal Drakensberg region – South Africa. Williams describes the mural, saying:

“The mural depicts a healing dance. In the center, a shaman is placed kneeling over a reclining patient. The surrounding line may represent a hut or an unexplained concept. The spread of arrows in the lower part of the mural may represent ‘arrows of sickness’ which an evil shaman was believed to shoot at people.”

Williams believes the shaman can protect people while they sleep, as he did during trance. He mentions in the same article that an informant said:

“Although the shaman is asleep, he watches what happens at night: because he wants to protect people from the things that come to kill them. Because of these things, he watches over people, for he knows that other shamans walk at night to attack people.”

3- James David Lewis-Williams

The truth is, we have not encountered speech similar to that in Williams’s text. It is known that the altered state of consciousness is linked to a journey to another dimension associated with bringing rain, and the healing shaman has another type of ritual he performs. Another matter is that the figure with the shaman is a woman, not a man—this is clear from the body anatomy. This woman is called the shaman’s protective woman and is with him when he enters an altered state of consciousness. This woman protects him from death and is capable of bringing him out of deep trance at the appropriate moment. In (Figure 4), a mural from the Acacus, we see the protective woman in the same posture, performing her role in protecting the shaman. Williams did not mention the state of erection, which is considered one of the signs accompanying the state of ecstasy. Strangely, the sticks and arrows in the ritual for the girl in the menstrual hut were for protection from arrows of sickness, and in the mural we are discussing, they are also for protection from arrows of sickness. We do not believe that arrows are suitable for use in all rituals and occasions.

4- Uan Muhuggiag, by shefa salem

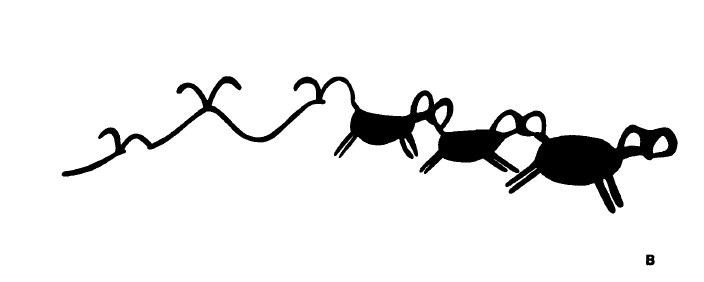

In a mural (Figure 5) from Uan Amil in the Acacus, we find the ritual for a girl’s puberty, which is an exact copy of the ritual found in South Africa. The difference is that we see a man holding the girl’s hand, leading her to a shelter specific to this ritual. This prevents any doubt that the ritual is for puberty and that the shelter is a menstrual hut. In front of the shelter, there is a woman receiving her to supervise her during her period of seclusion. Notably, everyone in the ritual is male, except for one woman who is tasked with supervising the girl. There is also a group of men wearing garments that Thomas A. Dowson interprets as “hybrid beings between human and animal possessing supernatural power.” Concerning the figures wearing garments: men carrying arrows and bows, and at the top, a shaman being assisted by two women on his journey back to his shelter. Most important of all is the rain bull that appears at the top of the mural.

The questions that now arise:

Why are arrows and bows present in a girl’s puberty ritual that has no relation to sickness or war? Why, in the menstrual hut mural from South Africa, is there an Eland, which is a rain animal? And in the Wan Amil mural, there is also a bull, which is a rain animal? And in the mural from Wadi Awis (the most important mural in our article), there are a bull and a wild sheep, both of which are rain animals?

In the context of Williams’s discussion about the girl in the menstrual hut, he says:

“The girl, during her seclusion, is required to eat and drink moderately. To ensure this, older women would place food in her mouth, and she would drink through a straw placed in a very small hole in an ostrich eggshell filled with water. If these practices are followed, all members of the tribe will eat and drink moderately in the future; there will be neither abundance nor famine. She had to treat rainwater with special respect. If she did not, she would suffer serious misfortunes, and the waterhole would dry up, leaving the entire tribe without water.”

The entire matter revolves around water and rain. We know well that the menstruating woman is present in rain rituals because the rain animal loves the scent of her blood. If it is the girl’s first menstruation, this means she must learn her duties towards the rain and the rain animal, and the woman supervising the girl must teach her how to enter the ritual of bringing rain and hunting the rain animal.

5- Uan Amil, by shefa salem

In the Wadi Awis mural, all the features are shamanic, starting from the geometric shape at the top left of the mural—a shape embodying water through dots and zigzags, which are symbols of rain and water. From the reclining shaman with a protective woman beside him, representing the circle of passage and return, to another shaman in a shelter or hut accompanied by the protective woman, and men wearing horns, with a rainbow in their midst. Symbols of wild sheep horns descend vertically on the right of the mural, symbolizing the shaman’s flight during the trance experience (Figure 6).

We now come to the issue of arrows and bows, which many link to war. There is a myth among the San people that says:

“The rain in the form of an Eland antelope is hunted with an arrow by one of the members of the ancient lineage of humans. Long ago, a man of the Early Race hunted the rain while it was grazing and calmly nibbling grass. At that time, the rain was like an Eland antelope. The man sneaked up to where the rain was and shot one of his arrows at it. The rain jumped when hit by the arrow and fled. The man went to the place where he had shot the rain, found the arrow, returned it to his hunting bag, and went back to camp. There he lay down and slept. Early in the morning, he told his companions that he had shot the rain with an arrow. They all went out tracking the rain. While they were tracking the wounded rain, a mist rose for a while. After that, they found the rain lying down. They approached it and immediately began cutting its meat. But when they placed the meat on the fire, it burned in the fire and suddenly disappeared. When they searched the embers for the meat, they found it had turned to ash. Finally, the meat disappeared, and the fire went out.”

6- ©David Lewis-Williams

This myth presents the relationship between the shaman, the arrow, and the bow. It also links the girl’s blood with the blood of the rain animal. In an article titled “Ethnography, Shamanism, and Rock Art in Far Western North America,” David S. Whitley says: “These embellished human petroglyphs (Figure 7) are self-portraits of shamans transformed into their supernatural personas, wearing ritual garments painted with symbols of their power (the geometric/entoptic images they saw during trance). The large central figure wears a quail feather headdress, a ritual headdress specific to rain shamans, and carries a bow and arrow, used in rain-bringing rituals.” These lines reveal that the bow and arrow are the oldest tools of the shaman for bringing rain, that the figures wearing garments are hybrid beings with supernatural power, and that the puberty ritual Lewis-Williams speaks of is a specific ritual for bringing rain by hunting it, as the man from the Early Race did. There is no conception whatsoever of the existence of war or combat.

7- ©David S. Whitley

Finally, we must talk about the musical instruments in the Wadi Awis mural. To the best of our knowledge, there is a great deal of literature on music in rock art, but here we have chosen the article “Musical Bows in Rock Art: In South Africa” written by Oliver Vogels and Tilman Lenssen-Erz. They discuss the use of bows for playing music, as in (Figure 8). Also, a book titled “Music and Trance: A Theory of the Relations Between Music and Possession” by Gilbert Rouget and Brunhilde Biebuyck. Drums are present in Afar and other areas of Libyan rock art, but we have not previously encountered anything indicating the presence of wind instruments in the Acacus or other areas. However, in the Wadi Awis mural, there are two wind instruments. One is decorated with ribbons, blown by a horned figure on the right of the mural. The second is blown by a woman next to the woman whose body forms the water hole in the center of the mural. In the book Music and Trance, the authors say: “Music has two effects: the first is triggering ecstasy, the second is maintaining it.”

The shaman begins his musical activity from the moment of his consecration. The shaman who reaches the point of playing music is the shaman who possesses all supernatural powers. “The shaman is the music of his entry into the state of ecstasy. In other words, the shaman enters a state of trance not by listening to others singing and drumming for him, but on the contrary, he sings and drums for himself.” The drum is not the only instrument the shaman uses. Some countries use a pair of sticks, in others a lyre, and among Native Americans, a rattle is used. The important thing is that the shaman uses music to summon spirits. But in the case of Wadi Awis, a wind instrument is used, which is a very rare case. It is the trance dance and summoning of spirits to hunt the rain, not war or combat as the mural suggests.

8- ©Gilbert Rouget

[1] The Medicine Dance of the ǃKung Bushmen- Lorna Marshall-Africa: Journal of the International African Institute, Vol. 39, No. 4 (Oct., 1969), pp. 347-381.

[2] Images of war: A problem in San rock art research-C. Campbell-World Archaeology-2015-p 255-268.

[3] Lbid.

[4] A Dream of Eland: An Unexplored Component of San Shamanism and Rock Art- J. D. Lewis-Williams- World Archaeology, Vol. 19, No. 2, Rock Art (Oct., 1987), pp. 165-177.

[5] Dots and Dashes: Cracking the Entoptic Code in Bushman Rock Paintings-Thomas A. Dowson-Goodwin Series, Vol. 6, Goodwin’s Legacy (Jun., 1989), pp. 84-94.

[6] BELIEVING AND SEEIN-an interpretation of symbolic meanings in southern San rock painting-ames David Lewis-Willia-University of Natal, Durban-1977.

[7] Lbid. 267.

[8] Ethnography, shamanism, and Far Western North American rock art- David S. Whitley- BOLETÍN DEL MUSEO CHILENO DE ARTE PRECOLOMBINO Vol. 28, n.º 1, 2023, pp. 275-299.

[9] Music and Trance: A Theory of the Relations between Music and Possession- Gilbert Rouget & Brunhilde Biebuyck-University of Chicago Press-1985- p 316.

[10] Lbid.126.

Mohammed Abdallah AlThrhuni

writer and researcher