The Greatest Land-Attached of His Era

Article: Land-Attached, Mohammed Abdallah altrhuni

The caravan, laden with all things strange and wondrous, entered through the great gate of Murzuq. People gazed at the throne carried by a massive camel, and they were astonished by its deep red color. The throne was a gift to be presented to the King of Bornu. Another camel carried something even more peculiar in the eyes of Murzuq’s inhabitants: a large pendulum clock. No one expected that box to hold time within it.

The young Dr. Nachtigal looked at Muhammad al-Qatruni and recalled the five-week walk from Tripoli to Murzuq. He thought that Muhammad al-Qatruni did not need a map or a compass to know the way. For him, the desert was utterly complete and present, like a white cloud glimpsed against the sky’s blue. For Nachtigal, however, it was an incredibly rich and violent fantasy.

Muhammad al-Qatruni was not given the title of explorer; he was referred to as “The Arab Guide”. Al-Qatruni did not think about his title or what was said of him; he left that matter to the desert sands and forgotten history books. Anyone who has studied the phases of the exploration of North Africa and the Sahara knows Muhammad al-Qatruni. He accompanied Heinrich Barth on his journey to Timbuktu and Kukawa, Karl Moritz von Beurmann on his trip to Bornu, Rohlfs on his journey to Bornu and from there to Mandara, accompanied Nachtigal on his expedition to Bornu, and Douvrier to the land of the Tuareg. Every European traveler advised those coming to the desert after them to have al-Qatruni as their guide.

Nachtigal says of Muhammad al-Qatruni in his book “Sahara und Sudan”:

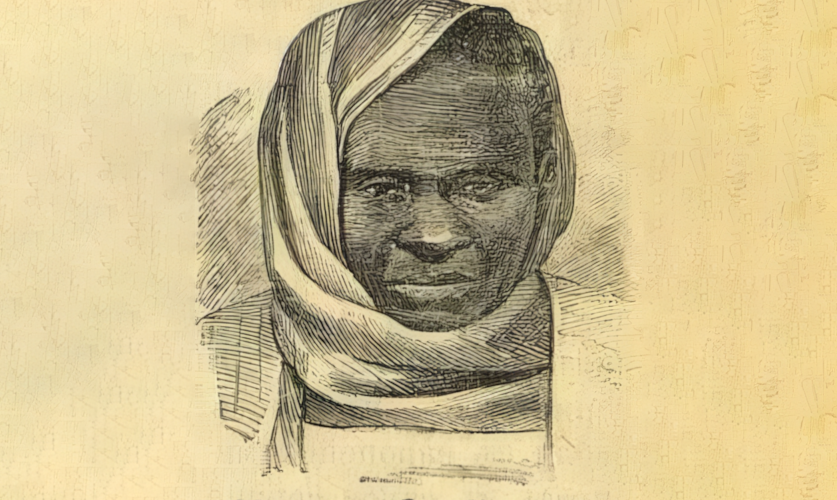

“It seems to me that my countrymen did not treat the respectable man Muhammad al-Qatruni with the fitting attention. He was Barth’s companion on his journey to Timbuktu, and he also accompanied Rohlfs to Bornu and Mandara. Nor did they pay attention to the white Tuareg camel he brought to his country from Bornu during his last journey. He came from his homeland, Fezzan, to accompany me, living near the capital Murzuq in the village of Dawjal, busy preparing the camel litters for the imminent journey. I looked upon his round black face with a certain awe tinged with respect, marked by countless wrinkles, his flat nose with wide nostrils, his toothless mouth, the sparse black-and-white hair of his beard, his large ears, and his loyal eyes. The elderly man Muhammad was not talkative, as I observed on repeated occasions in the years following my meeting with him, and he was a friendly man, not averse to enjoying life’s pleasures. Yet he rarely allowed his composure—a result of his extreme sensitivity and experience—to be disturbed or unsettled. He would answer my greetings with dignity and my expressions of happiness at making his personal acquaintance—which interrupted his work—by putting a small amount of roughly crushed green tobacco leaves from a small leather pouch into his mouth, and by breaking off a piece with his remaining teeth from a block of natron as a suitable corrective for the tobacco. Over the familiar, loose shirt of his homeland, he wore a warm woolen covering, also customary in Fezzan, which now hung down his back, away from his closely cropped head so as not to hinder his work, as he squatted on the straw with which he was stuffing the litters.” 1

All we know about al-Qatruni is that his family resided in Madrusah, from where they moved to Murzuq, and finally settled in Dawjal. No one knows the reasons for this movement from one place to another. From his childhood, Muhammad al-Qatruni understood the meaning of mobility, like a traveler drifting amidst the desert as a piece of wood floating in a sea of sand.

Each of these travelers whom Muhammad al-Qatruni accompanied, after their journey ended, would return to their countries carrying with them a distant, foreign, and overpowering place. But al-Qatruni would return to his home, carrying his large and spacious home within him. For them, the desert was forgotten and neglected – and this was true only in their impoverished mental map. But for al-Qatruni, the desert was a door wide open, and he was in it like a wild bird letting out its intimate cry.

No one knows how al-Qatruni became the greatest land-attached of his era. No one thought about how the path became his own while others were afraid to take another step. For the travelers, the desert was a cultural complement with an oriental flavor. For al-Qatruni, the desert was a spatial moment or a large desk covered by his memory with the color of sorrow.

Al-Qatruni did not think of these travelers as adventurers or spies, nor did he ponder their declared or secret objectives for these desert journeys. He did not have the time or knowledge to contemplate the realms of politics and ethics. All that concerned him was completing the mission, ensuring the safety of these travelers, and returning them to their land.

When al-Qatruni led Barth’s caravan, he was young, yet he had already traversed the entire eastern half of the Great Sahara. By the time he was at the head of Nachtigal’s caravan, he had traversed the entire Great Sahara. He was Barth’s chief servant, receiving a salary of four dollars per month, plus a bonus of fifty dollars upon completing the journey. Al-Qatruni lived through the desert’s dangers with Barth and protected him on many occasions. In Timbuktu, Barth’s house came under fire. Al-Qatruni loaded his rifle, and when Barth tried to stop him, he said:

“The Fulani must think we are cowards. If we do not stand as men, they will despise us.”

Drougou mentioned this incident in his memoirs about Barth’s journey and its events. Muhammad al-Qatruni was attached to a land that bore different names for the same dunes and rocky masses. He was not a geographer, but he had a geographical eye that knew its way to the journey’s end. He did not move to colonize another people or seize another land. He only wanted to hear the rhythm of the wind and the sound of his camel groaning with longing. He had a sensitivity towards the earth and felt that the world without the desert was sterile and dead. When he worked with Rohlfs, he had sworn to his wife that he would not undertake another journey, but he could not resist the call of the dunes and the madness of the wind and storms. This is the land-attached person, crossing borders with the spontaneity of the Bedouin. Muhammad al-Qatruni’s practice of travel was a creative subject without his knowing it. And when he connected with the land, he did not know the appropriate words to say; he only felt the sorrow of the distant gaze towards the dunes as he smiled that serene smile.

1 Nachtigal, Gustav. Sahara and Sudan: Tripoli and Fezzan. Translated by Allan G.B. Fisher and Humphrey J. Fisher, vol. 1, C. Hurst & Co., 1974.

Mohammed Abdallah AlThrhuni

writer and researcher