The Ash of Memory and the Invention of Meaning

Article: History, Hamza alfallah

Why must we re-examine the nature of history today? This question posits the poetics of return to the past as a realm open to narratives that transcend the linearity of events leading us to a closed cabinet of facts—those facts that resist the superposition and intermingling of humanities to achieve perceptions more biased toward understanding the human, who ignited the fire of primordial memory to invent meaning. He is a being who not only makes facts but also drifts in his existential sorrow far beyond merely grasping two sticks of wood to kindle the vitality of light in his cave for the flow of knowledge. But what knowledge is that? And what sensory necessity overwhelmed him for the long song and dance around the flame?

Perhaps this human thought as a free historian, and he was not seduced by scientific truth in its rigid form, but rather by its magical, layered strata—in what glimmers at the heart of the fire, what vanishes on the margins of his infinite horizon above the mountains, and what silence conceals in the ash of future generations from the flash of discovery.

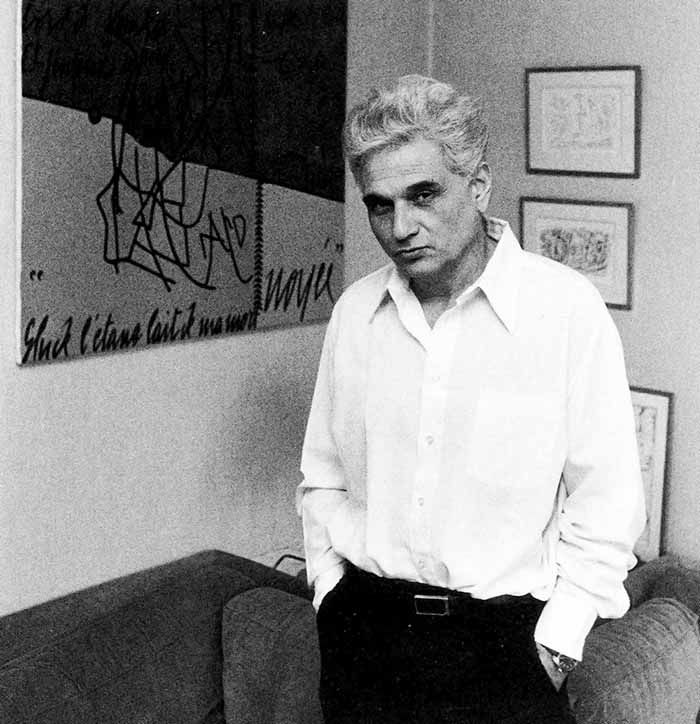

Reconfiguration and innovation in postmodernism are an alert intellectual process, interrogating historical truth and deconstructing its certainty. Jacques Derrida was among the first to draw attention to the fragility of meaning and the impossibility of capturing the origin in any historical text. Meanwhile, Michel Foucault pushed the history of ideas toward power, arguing that it is power that produces knowledge, demonstrating that narratives of the past are not entirely innocent of the networks of circumstances that produce them. Similarly, Hayden White, who contributed to founding the theory of “historical narrative,” offered a radical reading positing that history cannot be separated from its narrative structure, and that the historian, however neutral he claims to be, writes within literary frameworks that color his interpretation of events.

Our contemporary view of history is not satisfied by a comprehensive and final explanation, nor by mere juxtaposition with anthropology, psychology, sociology, geography, and philosophy. This deep, radical shift in the intellectual structure of interdisciplinarity is not satiated by neutrality; rather, it shatters the mirrors of static, declarative discourse in favor of an aesthetics that proclaims itself the heir to the collective memory of the narrative act. This aesthetics whispers through a language that invents the optimal text for reading history as a dynamic network of infinite probable paths.

Today, it can be said that breaking the traditional boundaries of history has become possible only through writing that reconstructs the past via multiple tools—from discourse analysis and image reading to data sciences. With these tools, our Libyan history can transform into a living substance, reshaped with every new discovery and with every different perspective that tells us the past is not a completed block. This contemplative gaze beyond the limits of the historical tale can make history an open project for understanding the human of the first fire, before being a closed project for understanding time. It becomes a critical practice not content with explanation alone, but one that questions the very questions themselves: What does it mean to write the past in a time when the tools of knowledge and the standards of truth are changing?

Hamza Alfallah

Writer and researcher