Acacus

In the far southwestern reaches of Libya, the earth’s first sentences were engraved. In the Tadrart Acacus, nature is read through shadow, through the grooves of light carved by wind into rock. There, upon the highest peaks, mountains are not merely elevations but breathing entities that exhale time. The awesome solitude is like a congregation of stone shepherds guarding the memory of myths, of hunters, of herds, and of women dancing upon the shores of fertility. A solitude where bodies transmuted into symbols long before history was invented from the narratives of primordial humans in the wombs of dark caves. Before every rock arch, as if they were portals declaring that existence requires no clamor to be complete. In those mountains, the cosmic origin of story returns in a state of wandering lived on the edge of the dense essence of the beginning—where boundaries held no meaning, time held no dominion, and words held no necessity.

Photographs by Tarek alhoni. This work is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International

The Acacus: A Fire That Awakens Dreams

Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari have a saying in Anti-Oedipus: “Stay in the desert long enough, and you will grasp the absolute.”

I spent my adolescence and youth waiting for a journey to the desert—this terrifying and astonishingly fragile place. I lived dreaming of sleeping on the fringe of the wind, of understanding the meaning of the unfinished moment. Nothing compares to embracing that vastness where the soul awakens. This part of my homeland knows what it means to sing a sorrowful song that makes dreams triumph.

On a day in 2007, I found myself drifting, like a drunken boat, toward the Acacus. All those with me on the journey—a dazzling kind of demise—were taken by the desert into its embrace, woven from grains of sand not yet fully formed. The wonderful Ahmed Al-Abeidi took upon himself the realization of a dream whose droplets he heard falling within his heart.

We left Tripoli for Ghadames, which lives the latent simplicity in the tone of time’s voice. There, Ahmed searched for a guide to make the earth speak in its own language. Hussein, the young man, only agreed to be our guide—who navigates by the sun and the stars—after sharing dinner with us. He had no choice but to help these hapless souls achieve their velvet dream.

All along the road from Ghadames to Ghat, he drove ahead of us. The “Toyota Fox” cut through the desert, its sinking wheels connected to a thousand enchantments in the earth, and nothing could stop it. Hussein didn’t speak to us; he gazed at the desert with ease, and would sit down after the transparent sound of the sun faded, along with the hum of the car engines. He would take his natah—a woolen mat of brilliant white wool—spread it out after lighting a fire, and begin preparing a cup of tea.

But this did not last long; after a gathering and conversation with him, we found him dancing to music on the roof of the Toyota. I have never forgotten the Acacus, nor Hussein, about whom I wrote many years later, in 2024. He became one of the characters in my novel, “The Death of Miss Alexandrine Tin in Libya.”

I remember now the moment Hussein stopped at the entrance to the Acacus and cried out: “This is the crossing point from earth to heaven.” We stepped out of the cars in a state of awe, like those who have entered a secret door suspended in the soul of the earth. I remember placing my hands on my head, wondering how one could envision such beauty without feeling the spray of salt tears on one’s lips.

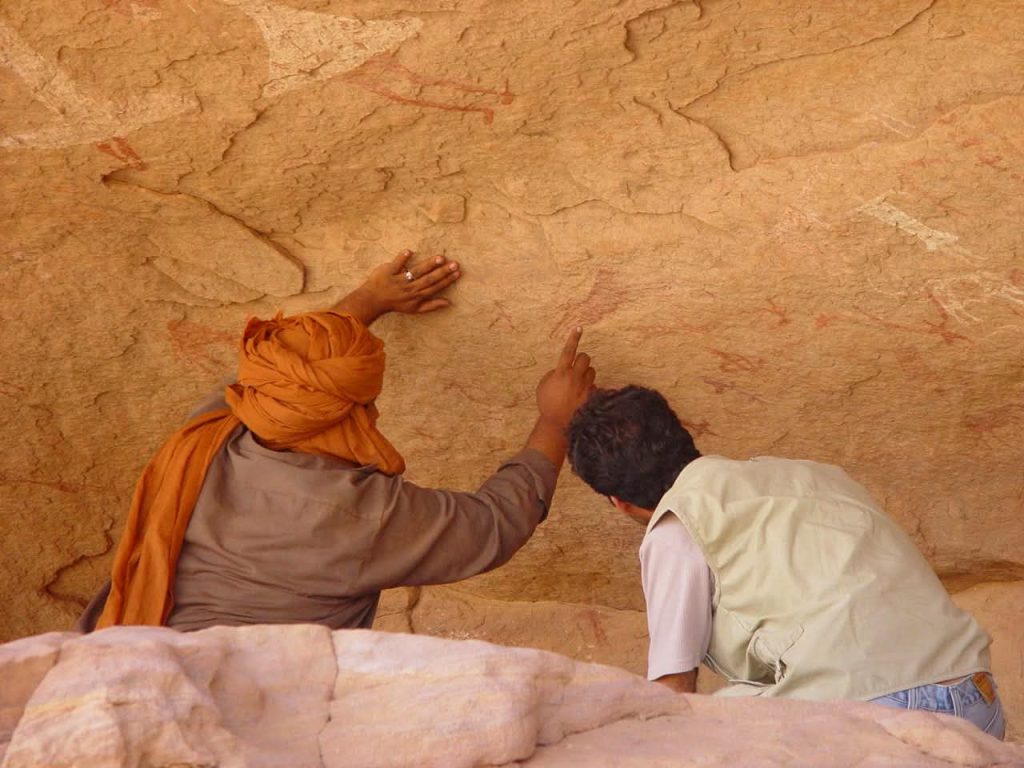

That was my encounter with those mountains, hearing their unique rhythm. Every mural I stood before was like the sound of a violin piercing my soul, once and forever.

Now I recall a famous saying I will never forget: “If you are saving money to travel, how many journeys might you miss? Columbus had no money to travel, yet he traveled.”

Tadrart Acacus is a range of rocky mountains located in southwestern Libya, within the Sahara Desert. The ancient city of Ghat is its nearest urban center. It is considered one of the oldest artistic centers in North Africa. It lies in the Fezzan region, which is connected to Tripoli in the north, Barqah in the south, the Republics of Niger and Chad to the west, and Algeria to the south.

The region’s terrain is predominantly desert, though it contains numerous valleys and oases. The landscape of this mountain range is distinguished by its rock arches and massive stone formations, including notable sites such as the **Afzeggar Arch** and the **Tin Khalja Arch**.

The area is also famed for its ancient caves and is rich in a collection of rock engravings and painted murals. These were designated a **UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1985** due to the significance of this rare form of rock art, which reflects the culture and records climatic changes in the region—some of which date back more than **12,000 years**.