Fashion in Prehistoric Libya

Article: anthropology, Mohammed Abdallah Altrhuni

Fashion is a cultural commodity and a social life. All commodities are cultural, but fashion presents an autobiography of societies. Fashion moves the world, and this is a truth that must be acknowledged. Fashion is sometimes antagonistic when it does not serve the goals of the world system, hence there is a call to replace it with fair, local, and anti-colonial taste clothing. First, we must agree that dress is not fashion. Dress is a social practice humans have engaged in for thousands of years, whereas fashion is an economic subject and a product of industrial capitalism. Margarita Rivière likens fashion to “a pervasive narrative that has mobilized people on a large scale in this era to see, buy, and embody this narrative in themselves.”

If we set aside the trivial and flashy appearances of consumer society, we must admit that fashion is necessary. Clothing has been an obsession for humans throughout their long history, and every society has established its own concepts of dress and its social status. There is sacred dress, war dress, and dress that expresses social function. In consumer societies, fashion appears for a consumerist motive. In third-world societies, if a local fashion industry emerges, the motive is historical, cultural, and also primal in some aspects. Because clothing has become a kind of media, the person from the third world wants clothing to present an image of their identity. This complicates the task of fashion workers in these countries because they are obligated to acquire historical, geographical, social, archaeological, anthropological, and ethnographic knowledge of their homelands. Without this knowledge, one cannot distinguish between what could be a source of inspiration or difference. In this context, knowledge is viewed as a process composed of understanding and interpretation.

The prominent aspect of fashion is that it forms the history of dialogue between humans and objects. Libyan rock art presents this historical dialogue, giving us a somewhat clear image of taste, culture, and lifestyle, not to mention other matters that fashion can provide a detailed report on, such as climatic changes, shifts in dress methods, dealing with the arid environment, differences between pastoralists’, hunters’, and foragers’ clothing, differences between genders’ clothing, the prominence of certain garments indicating religious and social status, in addition to men’s and women’s adornment. We deal with rock art murals as visual material (“images”) without discussing the intention of the artist who engraved or painted them on the wall, in addition to taking the intentions and ideology of the photographer into account. Therefore, there is a compounded interpretive problem when it comes to the image as research material in rock art. There is the eye of the one who drew or engraved the mural, and the eye of the photographer with their modern culture. There is the surface of the photographic image and also the depth of the wall from which spirits slip into the other world. Yet, the photograph remains part of the fieldwork and is useful when read in its context.

Previously, since the discovery of Altamira, hand copying was the followed field procedure. Later, transparent plastic sheets stuck to the wall were used, where the researcher would reproduce the mural. In both cases, it was impossible to avoid errors that could reach the level of forgery. The photograph, due to its acute focus, helps us see all details more accurately. Despite this great accuracy, the matter seems extremely difficult because the field researcher is usually preoccupied with the text they will write, not the image ready for viewing. Also, the tool itself requires us to learn how to respond to it with visual precision.

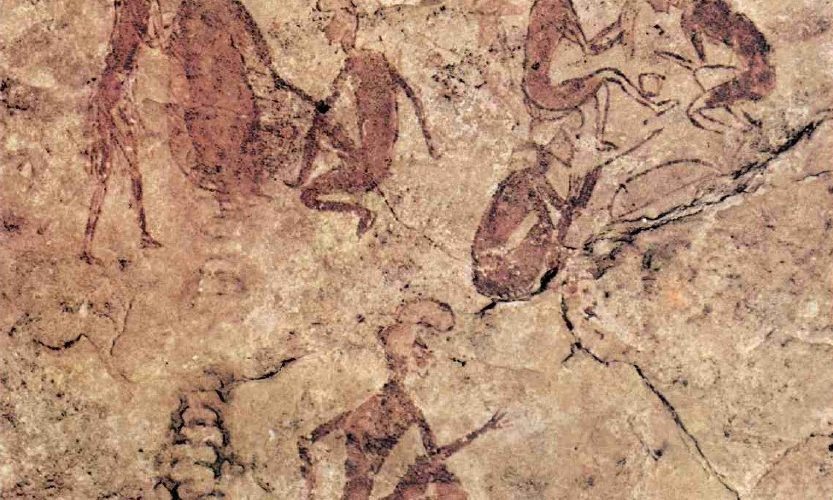

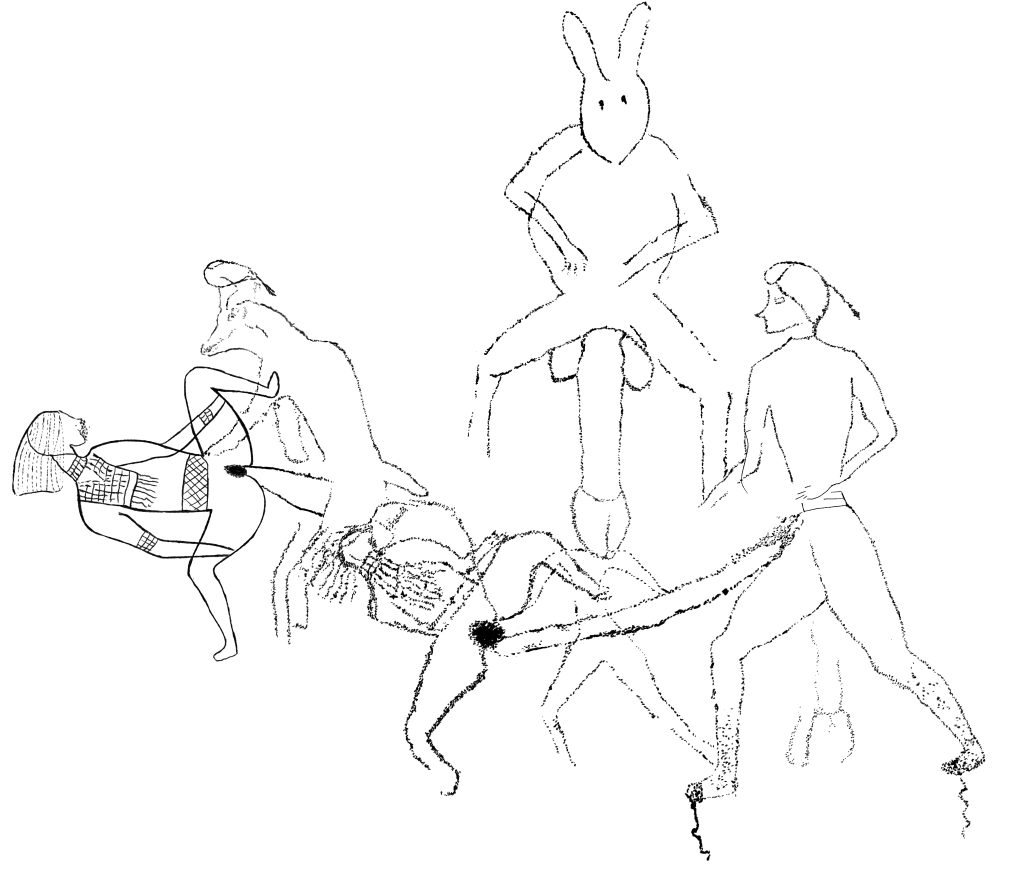

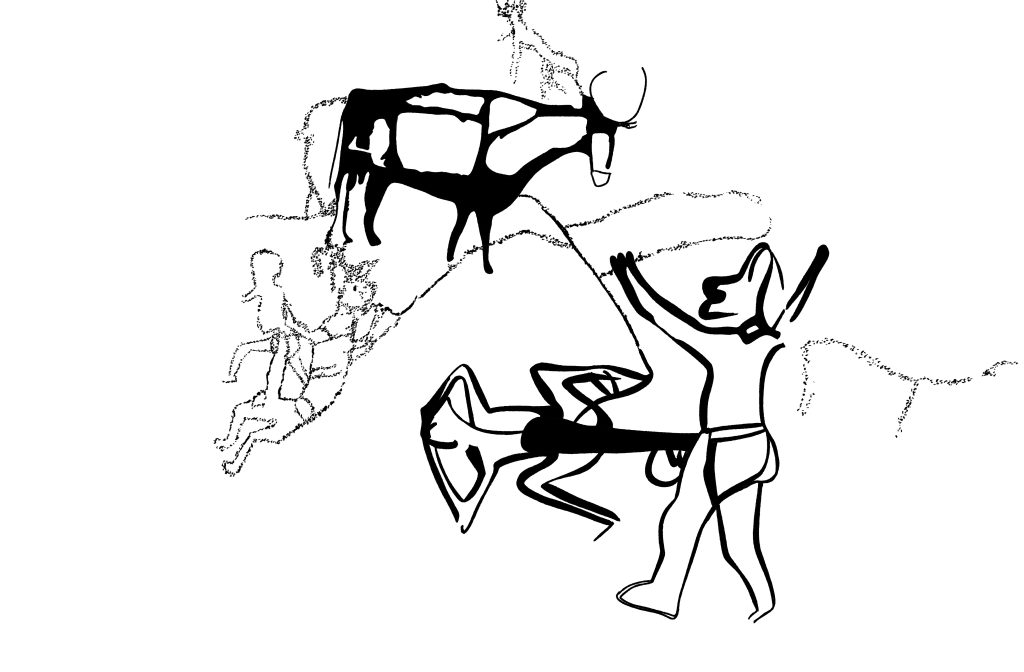

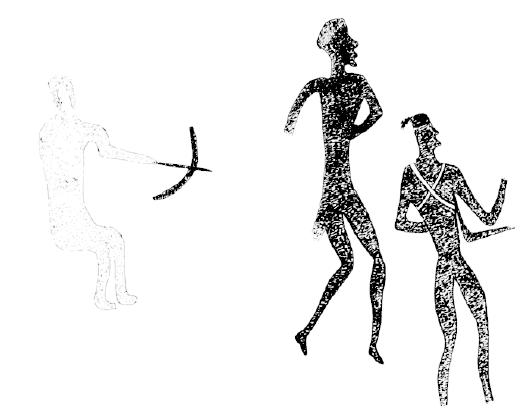

In this study, we will use the photograph as a tool for research and interpretation. It is a means to record abundant information and details authentically and quickly. Often, we return to images that were marginal to the photographer, outside their frame of interest at that moment, or in other words, an image captured for one purpose can be used with another objective and a different perspective. The image is an ethnographic condition that reveals a culture; it is a field of information and a space for exchanging messages. These messages change with the change in our understanding and the expansion of our information about the image’s subject. As an example, in (Figure 1), an image from Fabrizio Mori’s book “Tadrart Acacus”, a scene from Tin Lalan from the Old Pastoral Period, which Mori placed under the title: “A Coupling Scene.” Mori says about this image:

“In this coupling scene we see a woman lying on her left side; her lower limbs are spread apart and her hands are placed upon them. The face is shown only in profile, while the rest of the body is in a frontal position. This posture highlights some features such as form, posture, ornaments, and the care with which the drawing was executed. The hair hangs loose in dotted parallel lines. The facial features have disappeared or been damaged with rock fragments. A necklace in a net pattern is clearly visible. The neck is long and thin, separated from wide shoulders from which hangs what resembles a rectangular, net-patterned bodice with parallel fringes, leaving part of the neck bare in an acute angle shape. A bracelet is seen on the right forearm and on the left wrist of the same style. The attire is completed by a wide belt wrapped around the waist. No other ornaments or clothes appear on the body, nor are the breasts depicted.”

1- tin lalan ©Mori

Drawing by Shefa salem

Mori describes the necklace as net-patterned and the bodice as rectangular and net-patterned, also a bracelet on the right forearm and on the left wrist of the same style (meaning net-patterned). This is in addition to the loose hair hanging in dotted parallel lines. Is this net adornment truly jewelry? It cannot possibly be jewelry. If it were jewelry, we could say that the net on the leg of the large figure (Figure2) is jewelry. The net is considered a symbol of shamanism and appears during the shaman’s trance. J.D. Lewis-Williams and T.A. Dowson state: The first stage of trance is characterized by internal eye phenomena. Six geometric forms can be found in internal visions: dots, zigzags, grids, parallel wavy lines, and honeycomb patterns. Also, his statement “hair hanging loose in dotted parallel lines” – these dots are, in fact, one of the symbols of shamanism. The most important work the shaman performs for their community is ascending to the house of water to bring rain.

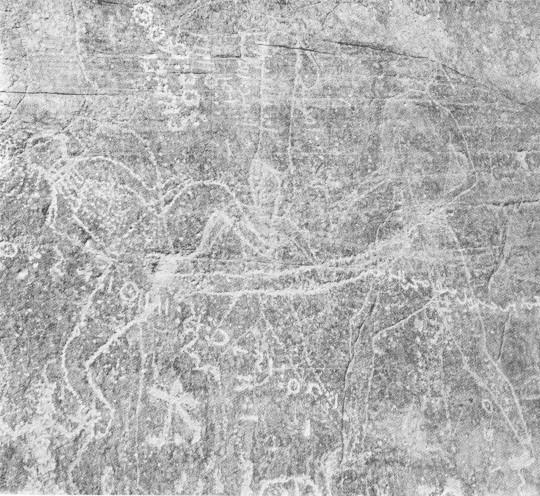

Also, the man (Figure 3) whom Mori suggests is coupling with the reclining woman, wearing an animal head as a mask, is a hybrid being. According to Thomas A. Dowson, this being is interpreted in shamanic beliefs as the shaman transformed into the animal possessing supernatural power. As for the sexual subject, according to I.M. Lewis in an article titled “Trance, Possession, Shamanism and Sex,” it is nothing more than a symbolic image of the ecstatic state in which the shaman enters trance. The mural is, in fact, merely a simulation of the shaman coupling with the helping spirit during trance. This spirit is usually a woman and is called the protective spirit because she defends the shaman against evil spirits trying to prevent him from reaching the house of water. This is just a message describing the shaman’s state and the ecstasy he feels during his trance journey. Evidence for this is the exaggerated size of the genitalia, which gives us a sense that something else is intended. Mori also believes the facial features are damaged, whereas the woman is bleeding from her nose, which in shamanism indicates entering trance.

2- Anshal, ©Mori

©tara/ david coulson Copyright TARA/ David Coulson

Drawing by Shefa salem

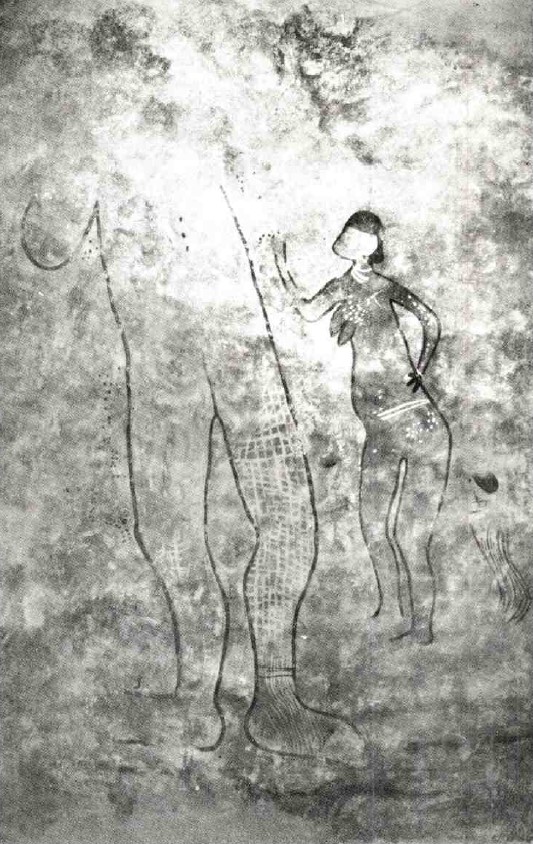

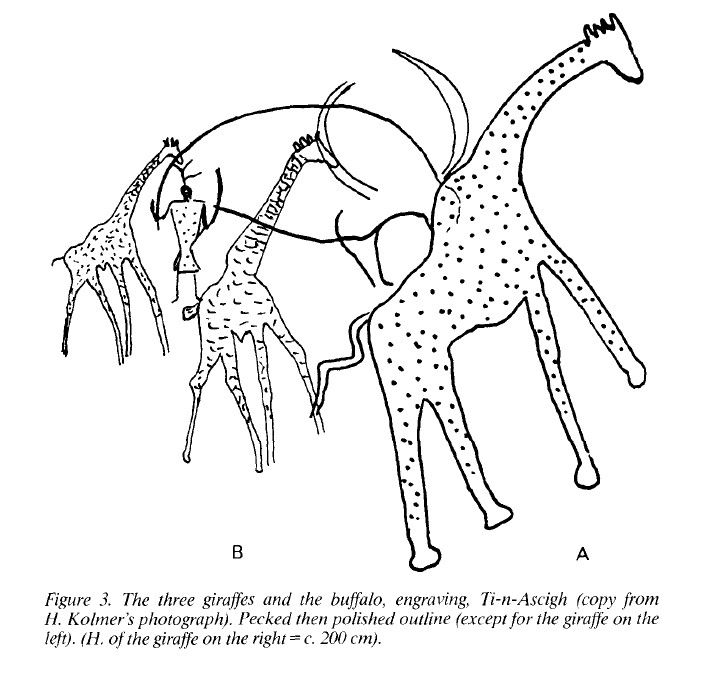

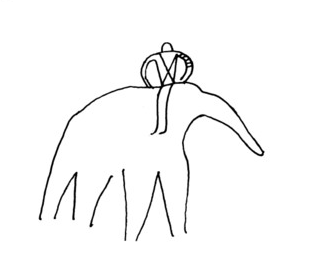

This is just an example of how understanding changes, and with it, the message the image intends to convey changes. What Mori sees as jewelry, adornment, and fashion of that era is nothing but religious and shamanic ritual symbols. Wearing clothes and adornment in prehistory is nothing more than a declaration that someone is performing a specific action. Masks, for example, can be viewed as merely part of the dress, or thought of as a symbol that changes a person’s identity metaphysically to qualify them for a ritual role. This does not mean that clothing was the focus and concern of prehistoric artists in all periods. For example, in the Period of Large African Animals, dating to the Pleistocene (Figure 4), the artist was very interested in engraving large animals: elephant, rhinoceros, giraffe, ostrich. If humans appear in these scenes, they are very small compared to the animal. In a scene from Ti-n-ascigh in the Acacus showing three giraffes, a buffalo, and a small person wearing a garment made from spotted animal skin, the garment reveals the arms and legs in the style of ancient pastoralists’ clothing. In contrast, in the Horse Period, the last period of prehistory, we find the artist interested in clothing and the posture of the person in the mural. As an example, an image from western Afar in the Acacus shows a woman wearing a short dress with her waist cinched by a white belt (Figure 5). What catches attention are the rings on her very slender fingers, multiple bracelets on her arms, what resembles anklets on her feet, a head covering, her neck adorned with a necklace, and she holds in her hand what could be a bag or something similar. This is not all; the truly strange thing is her posing stance, no different from any fashion model today. The Horse Period is considered a period of rock art decline, but in this specific period, humans became the focus of attention after the disappearance of large animals due to aridity.

4- ©A. Muzzolini,1991

5- Afar, Drawing by Shefa salem

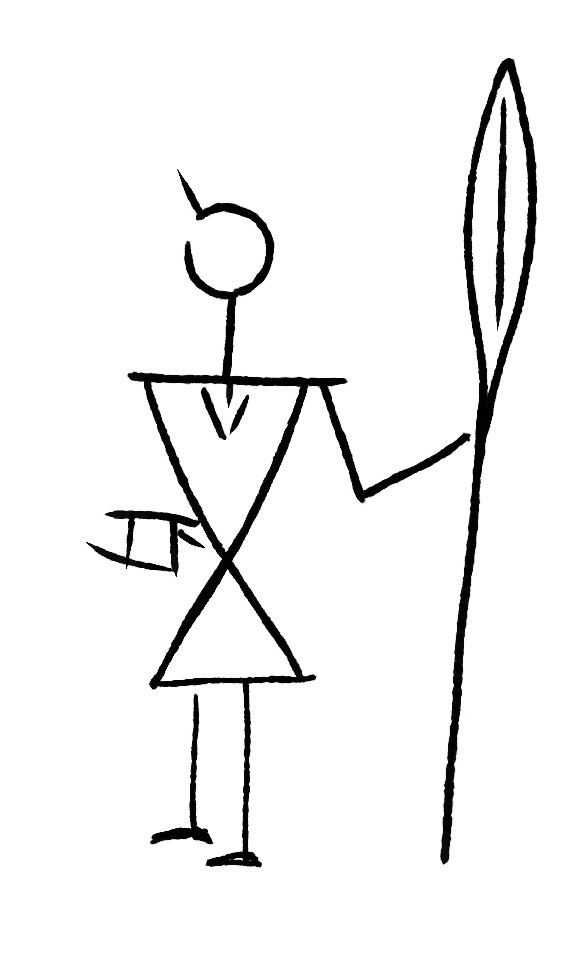

In Wadi Awis, we find another image of a woman wearing the same type of clothing (Figure 6): a short tunic cinched at the waist, ending at mid-thigh. Her right hand holds a stick, and something resembling a bag is hanging from her arm. From her left arm dangles something like a leather piece. The similarity in clothing indicates that the short tunic cinched at the belt was the fashion of that period in different places of the Acacus region. It must be known that this tunic was also worn by men. For this reason, the prehistoric artist shows breasts in a triangular shape on the right and left of the body to differentiate between genders. The tunic covered the entire upper body, and the appearance of breasts on the right and left is a symbol of females in the murals. In the Horse Period, it is known that the heads of figures resemble sticks, and their anatomy is bi-triangular (Figure 7).

6- Wadi Awis

7- Wadi el-Ajial

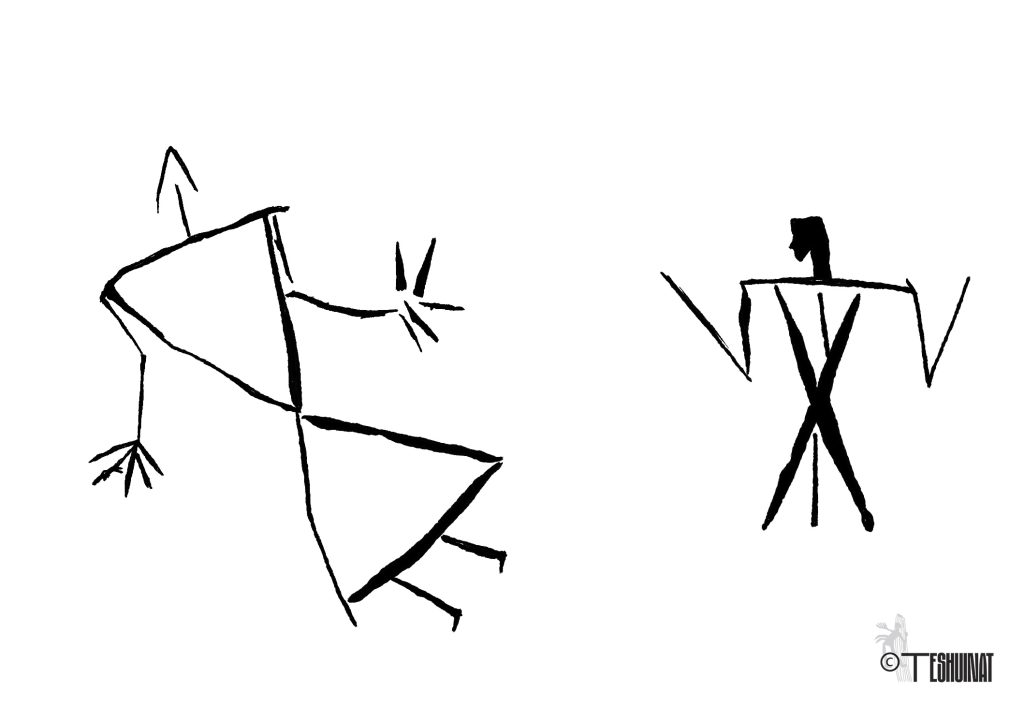

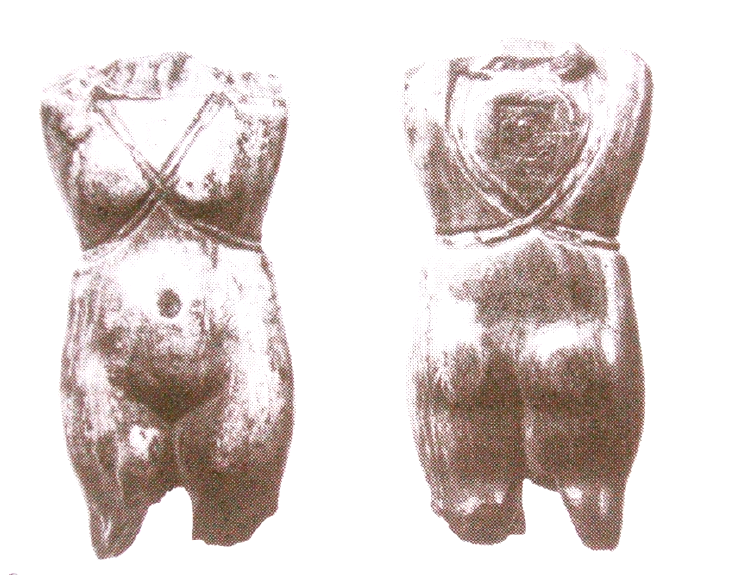

Rock art in this period is accused of stiffness, lacking that movement embodied by large animals. The truth is that this period focused on making the person’s image photographic; what is believed to be stiffness is actually the beginning of thinking about the photographic image in which movement disappears. The bi-triangular style is not new, as some believe; it is inspired by the crossed belts found in the Period of Large African Animals (Figure 8 a, b, c) from the Acacus. These belts used to appear only on the chest, but they transformed into a clothing style in all prehistoric periods and appeared directly in the Horse Period. The bi-triangular garment set evolved on a symbolic religious basis, not merely a transient change in dressing style; it is a symbol of Libyan identity from the beginning.

8-A- Tadrart Acacus, ©Léone Allard-Huard

8-B- Tadrart Acacus, ©Léone Allard-Huard

8-C- Tadrart Acacus, ©Léone Allard-Huard

In (Figure 9), two sculptures of two Libyans wearing crossed belts: one in the Louvre Museum – France, the other in Cairo. The straps consist of two leather bands wrapped around the body so that they cross in the middle of the chest. Each band is divided lengthwise into three distinct zones, with a series of very close horizontal lines in the center, and circular or quadrangular patterns arranged regularly on the edge.

9- ©Musée du Louvre, Paris.

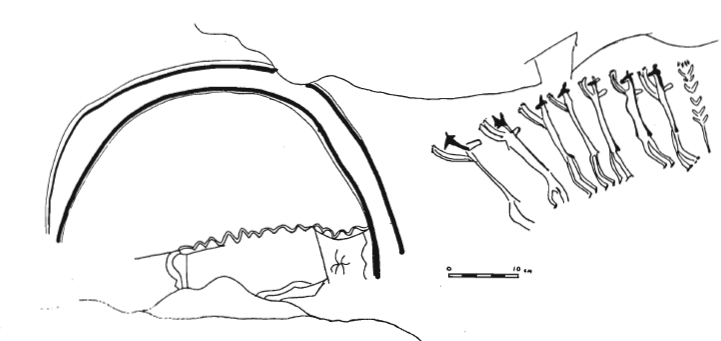

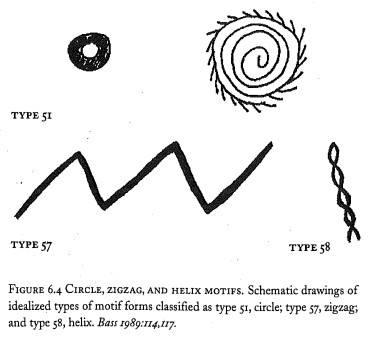

The triangle is a symbol of water, and the zigzag that appears in the form of adjacent triangles is a symbol of water in prehistory. In (Figures 10 and 11), we clearly see this specific water symbol in murals from different places around the world. In Libya, the triangle appears as a symbol for mountain and water or a symbol for the mountain of water.

10- southAfrica, ©woodhouse.

11- ©David S. Whitley and Lawrence L. Loendorf, editors.

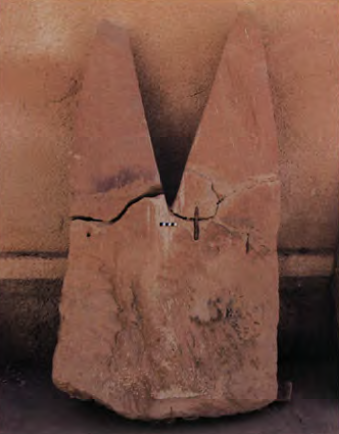

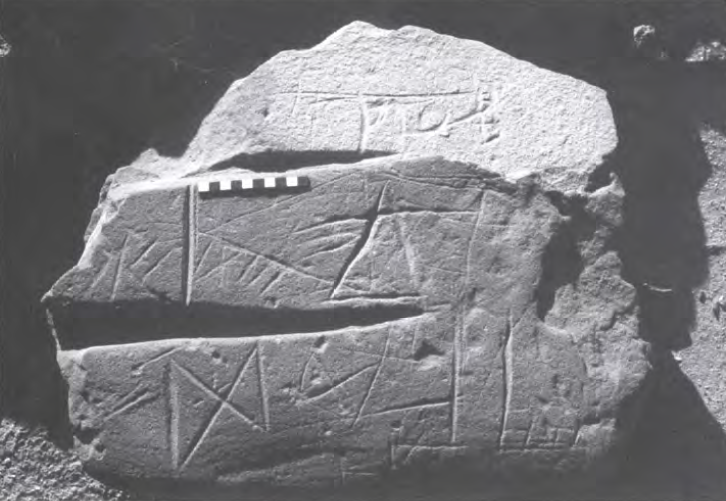

In (Figure 12), an image of a tomb marker from Garama, it takes the triangular shape symbolizing the mountain of water. In (Figure 13), bi-triangular symbols engraved on the marker appear; perhaps the engraver hoped the deceased would reach the mountain of water in peace. Whatever the case, interest in the subject of clothing began to clearly appear in the Horse Period, especially the first millennium BC. Crossed belts appeared as a style in drawing and engraving figures, meaning that water and its symbols in the arid period transformed from mere simple symbols into major symbols.

12- ©THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF FAZZAN

13- ©THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF FAZZAN

This change was not exclusive to men only; women also wore dresses of the bi-triangular type, but dispensing with the skirt and replacing it with a long dress cinched at the waist, as in (Figure 14). In the Old Pastoral Period, clothing for men and women was very similar, often consisting of what resembled a long dress cinched at the waist to form a bi-triangular shape (Figure 15). In the same period, hunters’ clothing shows a fundamental difference, as in (Figure 16) from Uan Imil in the Acacus, where we find a skirt made of animal skin in a net pattern and a very distinctive style, but even this skirt gives us a sense that it is within the framework of the bi-triangular fashion world.

14- Anshal

15- Tassili

16- uan Amil

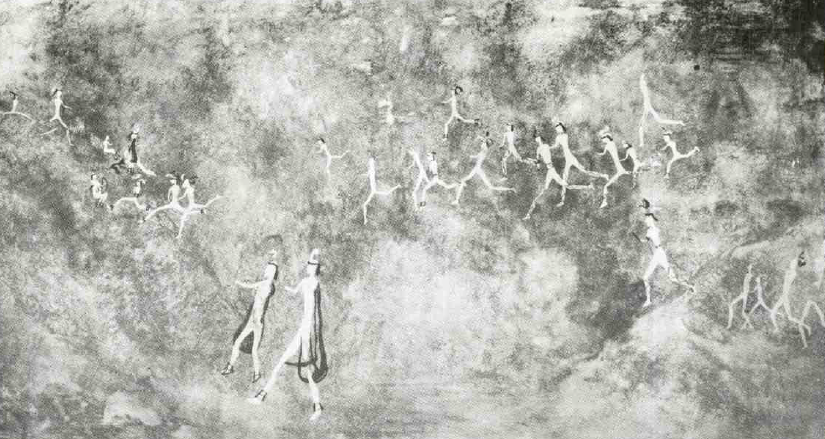

In the Modern Pastoral Period, which overlaps with the Horse Period, new models of clothing appeared (Figure 17). In this model, men drawn in white and yellowish-brown wear a cloak on the back and place a headband adorned with a feather. We also find this model in Wadi Raharmellen, with the difference that the cloak in this model is tied at the knees. These figures are drawn in profile, contrary to the usual in the Horse Period. Mori placed this group, which he believes is Mediterranean, in the Middle Pastoral Period, which some scholars did not accept. It is believed that this group invaded Uan Imil and Ti-n-anneuin, perhaps said because these forms have blond hair and are not drawn in a fully bi-triangular style. However, their small round shields place them within the style of the Libyan warrior.

17- Uan Amil

In Uan Muhuggiag, a mural with many people drawn in white, and only two of them are covered by robes (Figure 18). ). Mori says about this mural that it is of a Pharaonic type, and I find no reasonable reason to make them Pharaohs except Mori’s imagination. Whatever the case, this type of clothing appeared in Uan Muhuggiag, Ti-n-anneuin, Uan Imil, and Wadi Raharmellen, meaning it was widespread in the Acacus. The presence of feathers on their heads and the type of their dress make them from a specific class of society, or perhaps they are from the religious class supervising rituals. This type of clothing does not completely remove its wearers from the bi-triangular style, and it may be a development to distinguish the clothing of a specific category or ethnicity of people.

18- Uan Muhuggiag, ©Mori.

The triangle as a pattern is a style globally known as “the Libyan Warrior style.” This style is geometric schematic, favoring straight lines and sharp angles. Figures in this style often appear armed, hence the name of this style, but not always. Murals have been found with figures in the same style but unarmed. This style exists in the Acacus (Figure 19), Matkhandoush (Figure 20), Oued el-Ajial (Figure 21), northern Fezzan, and is almost present throughout the Libyan desert. These figures usually wear mid-length tunics, tight at the waist, forming a bi-triangular shape. This style is often linked to the Horse Period, warriors, and horse-drawn chariots. There is also a link between replacing the bow and arrow with metal-tipped spears and this style. But the truth is that the triangle was a symbol of water, fertility, and spiritual ascension in the Acacus and elsewhere. From this perspective, we must realize that the Horse Period is, in fact, the period of photography in Libyan rock art, a period in which prehistoric artists addressed the subject of identity in dress.

20- Wadi el-Ajial

21- Wadi I-n-Erahar, Messak

21- Wadi I-n-Erahar, Messak

Finally, we must recall the distinctive hairstyle of our ancient ancestors (Figure 22 and 23). Just as the bi-triangular dress was not exclusive to men, the hairstyle was also shared between genders.

22- Uan Amil, Shefa salem

23- Uan Amil, Shefa salem

Mohammed Abdallah AlThrhuni

writer and researcher