A Glimpse into Shamanism in Libya

1

In the early 1850s, the priest Avvakum was making his way to the land of the Evenki reindeer herders. As he walked, feeling the cold air fill his lungs, he climbed a small hill. The words of the Patriarch of the Russian Orthodox Church, exiling him to the heart of Siberia, imposed themselves on his thoughts. His mind held no endless, dissonant conflict, no confusing words difficult to defeat; only a feeling of bitterness floated on the surface of his transparent soul.

Before his arrival, no one had heard the word “shaman,” which resembles a silent essence. But after Avvakum’s execution in 1682 on charges of heresy, the reindeer herders came to know well the cosmic concepts underpinning the word “shaman”—concepts drawn by the hand of dream and labeled by anthropologists as Shamanic Studies. As Russia was traversed by missionaries, exiles, Tsarist agents, and European travelers, all highly educated, more stories of shamanic practices and beliefs were recorded. The tales told by the early travelers were astounding and generated intense interest in Russia and Europe. A fragmented image emerged of a world of spirits, where everything was alive and teeming with spirits, animals, and natural landmarks. All aspects of material life were linked to these beings: sickness and health, the provision of food and shelter, success in hunting, and the welfare of the community. Therefore, maintaining a good relationship with these spirits was of utmost importance.

The most prominent travelers’ stories concerned distinctive individuals who achieved states of trance and ecstasy to send their spirits to communicate with these supernatural beings. Avvakum’s story is mentioned in the book The Archaeology of Altered States: Shamanism and Material Culture, edited by Neil S. Price. Strangely enough, the writer states: “The essential question is whether we can truly speak of shamanism outside the Arctic. Here we enter a broader framework of interpretation, starting from Siberia and the Arctic region on a holistic, graded scale to include shamanic features in the ritual practices of South America, Oceania, and Africa (particularly controversial).”¹

Why is Africa particularly controversial? Because shamanism there spans thousands of years, and its presence may extend back to the end of the Pleistocene. The controversy lies in questioning the beautiful story of the priest Avvakum and the notion that shamanic religion originated in prehistoric Russia. The slightest look at the rock art in Southern Africa, and Libya specifically, makes the claim that shamanism began in 1682 AD with its cradle in Russia a mere joke. Shamanism in Africa has been neglected, a fact admitted by Mircea Eliade himself, who was largely responsible for popularizing the concept of shamanism, saying, “We have overlooked Africa.”2 Strangely, an anthropologist like Luc de Heusch states that shamanism is rare in Africa, while a writer like Michel Leiris, who visited, confirms its widespread presence there.

In our book, “The Land of the Garamantes,” we documented the spread of shamanic religion in prehistoric Libya, emphasizing that this religion is, in fact, a religion of rain. The most important task for a shaman in their community was to bring rain. Here, we will briefly outline the main pillars of shamanism and present some similarities between shamanism in Libya, Southern Africa, and other parts of the world.

2

The religion of rain revolves around the shaman. They are the only ones who know and master the experience of the trance, the only ones capable of identifying with spirits from the other world and painting its murals after returning from the trance. This transition from one world to another occurs through two means: first, the shaman summons helper entities which they control and communicate with; second, they send their spirit to the other world during the trance to communicate with supernatural power.

Drs. Lewis-Williams and T. A. Dowson base their understanding of Southern African rock art on a neuropsychological model of trance. This model is divided into three stages:

- Stage One: Phenomena of the eye’s interior. Six geometric forms can be found in internal visions: dots, zigzagging lines, grids, wavy parallel lines, and honeycomb patterns.

- Stage Two: The mind attempts to rationalize the forms to give them meaning and organize itself. In this stage, the shaman feels as if they are passing through a tunnel or being pulled into a vortex.

- Stage Three: The shaman experiences astounding hallucinations that engage all five senses in a somewhat confusing manner. In this world of trance, the shaman can travel and soar in the air, encountering animals and supernatural beings—both human and animal. They can also transform themselves into an animal and fully identify with it.

The shaman’s journey to other worlds depends on their ability to voluntarily enter an altered state of consciousness. During the trance, the shaman travels to another dimension and interacts with entities for the benefit of their community. It can be said that the shamanic journey is a journey of the spirit, a passage between a visible, real world and an invisible, spiritual one. To embark on the journey, there must be a vision, a helper animal, and the harnessing of supernatural power. The shaman’s spirit enters through a hole called Al-Qulta, then proceeds through a tunnel to the other world. Al-Qulta is a sacred pit; it is the shaman’s spirit after death, falling to earth in the form of a star that creates a water hole. It is the same pit from which the shaman reemerges after returning from the trance.

Before the journey, a trance dance ritual must be performed, through which the shaman enters an altered state of consciousness. This dance is usually accompanied by a nosebleed, after which the shaman enters the trance. At the end of the ritual, they are usually lying on their back, feeling as if they are underwater and their spirit has left their body. In this state, they are half-alive and half-dead, and may never return from their journey. The moment the shaman’s spirit ascends, there is always a woman safeguarding his life during the trance, known as the protecting woman.

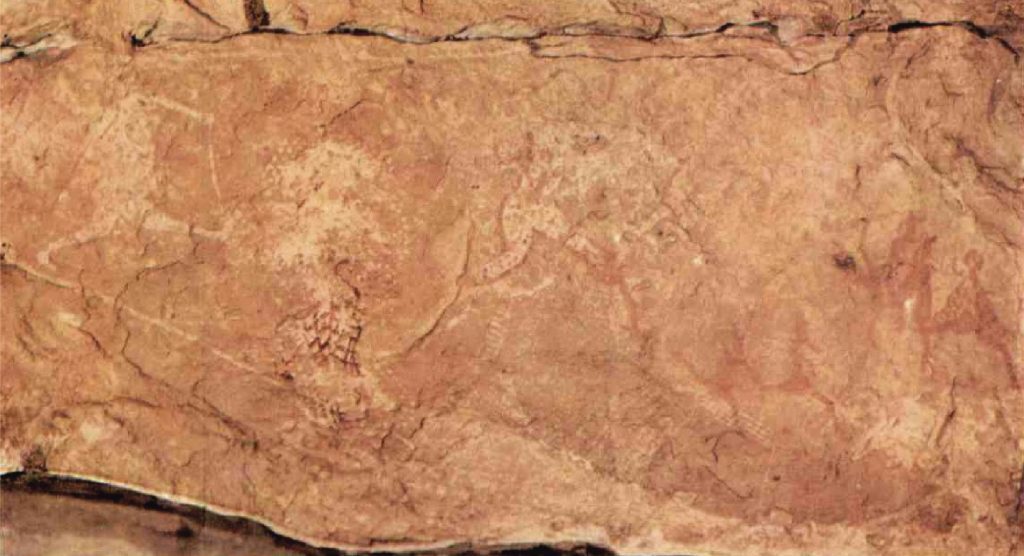

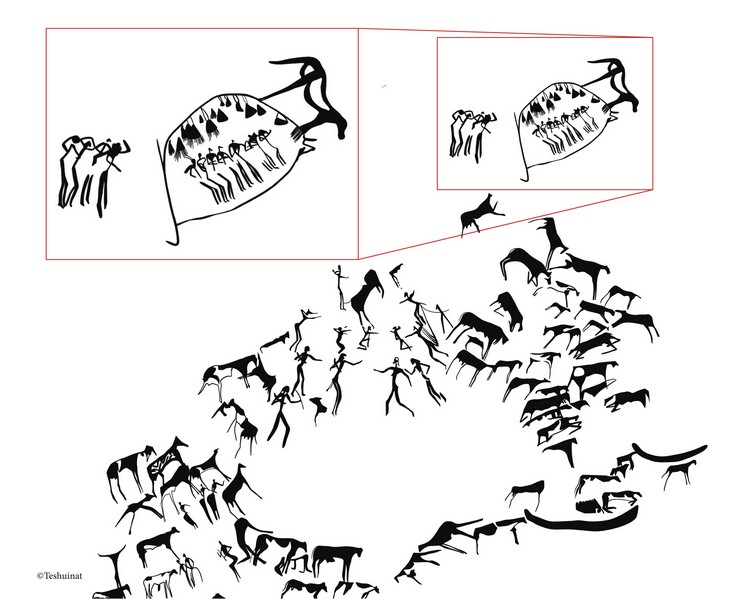

After analyzing an illustration from Fabrizio Mori’s book “Tadrart Acacus,” titled “A scene with a dead man in a reclining position at the end of the Round Heads period,” we found these rituals complete (Figure 1). The scene shows the trance dance, the shaman in a trance state, and beside him the protecting woman and the rain animal (which we will discuss later). We note the geometric shape representing a grid on the shaman’s body, in addition to dots and parallel lines, which are what the shaman sees in the first stage of trance.

Fig.1.1 (Mori,1965).

Fig.1.2 Copy of the wall, Uan Muhuggiag, Libya.

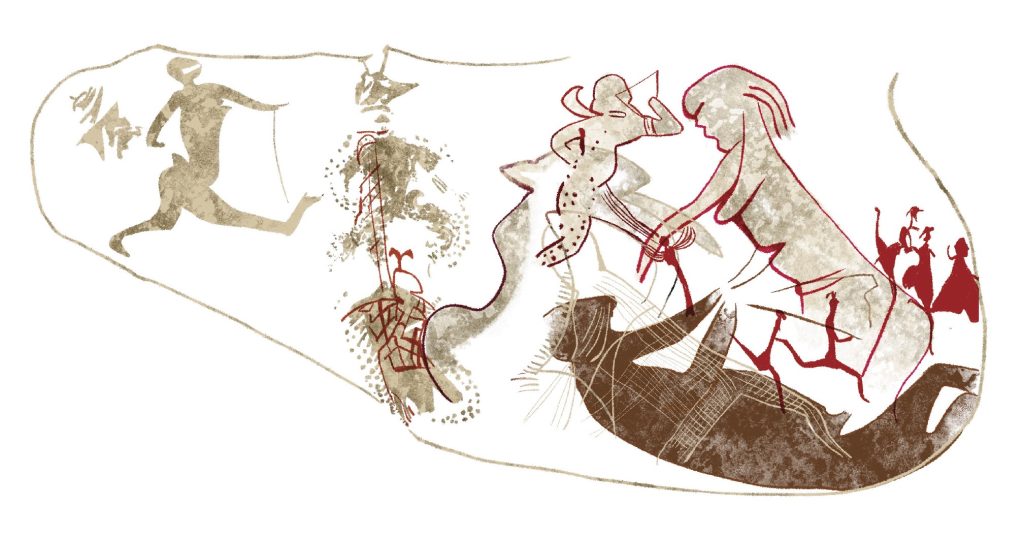

In (Figure 2), we find two scenes in the same context as we found in the Acacus. The upper one is from Southern Africa, showing the shaman in a trance with the woman helping him return. The second scene is from Jebel Al-Awenat in Libya, also showing the shaman in a trance, with a woman performing the same role beside him. These are just simple examples of the unity of shamanic religion in many parts of Africa.

Fig.2

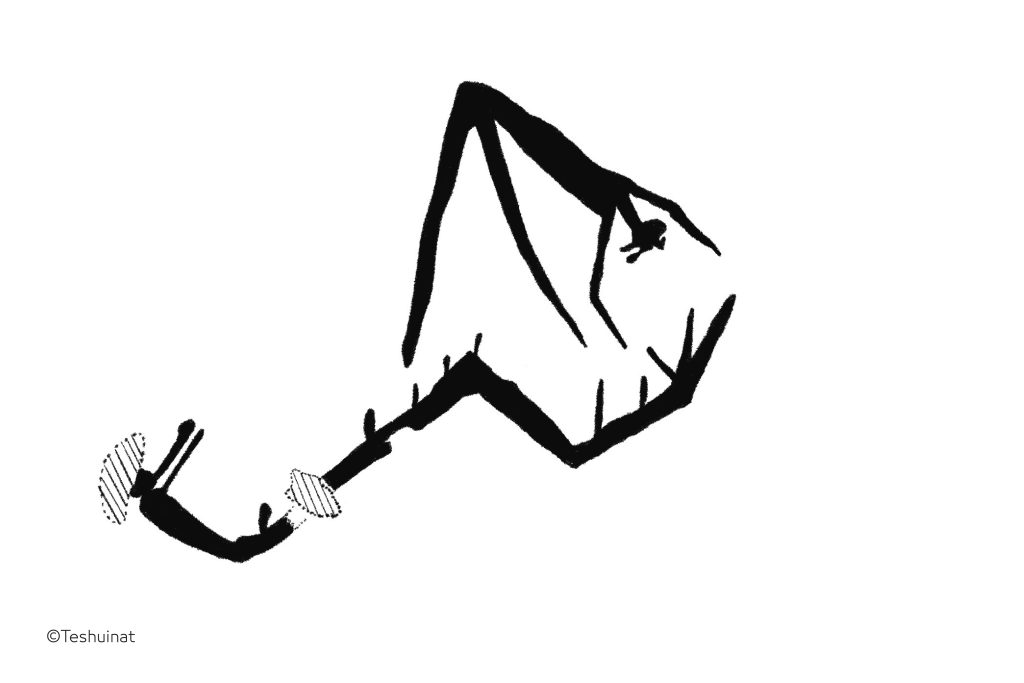

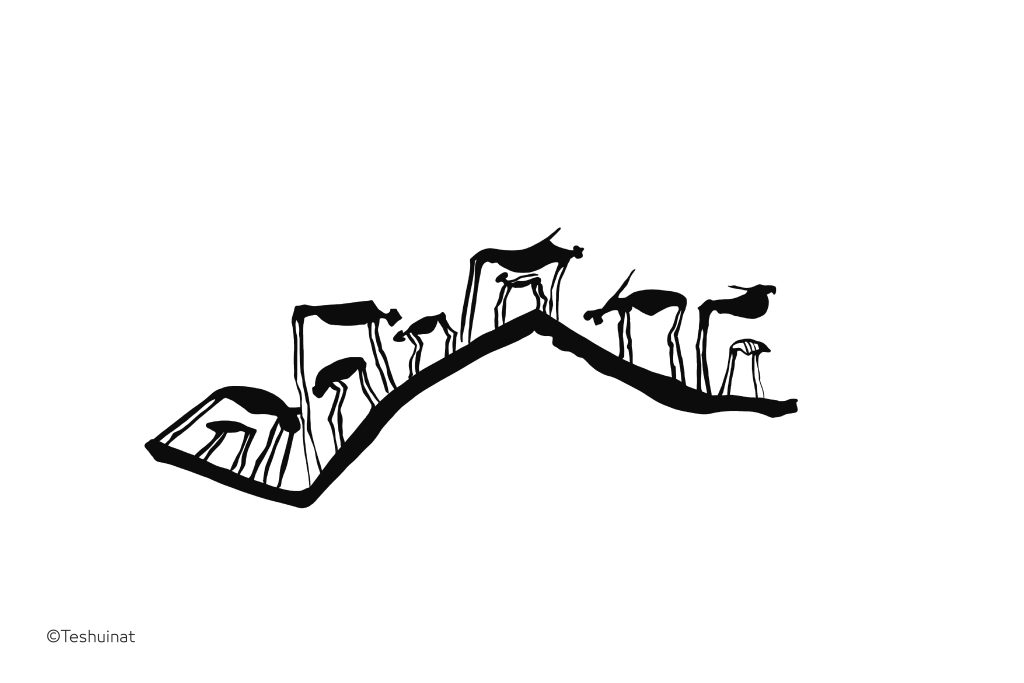

When the shaman ascends to the water house, his spirit climbs threads of light; in other cases, he transforms into a bird. In (Figure 3) from uan Afuda in the Acacus, the shaman is shown on his way to transforming into a bird. In (Figure 4) from Southern Africa, the shaman transforms into a bird, and the scene shows the stages of this transformation. There is another scene from Southern Africa (Figure 5) also showing the transformation from human to bird. These similarities and repeated motifs prove that shamanism is not merely a set of rituals, but a prehistoric religion, and the most important part of this religion is the shaman and his ability to bring rain.

Fig.3 Uan afuda shelter, Teshuinat, Libya

Fig.4 Bushman rock art, South Africa.

Fig.5 Aliwal North, South Africa.

3

Life in prehistory entirely depended on rain. Fruits, grass, grazing, hunting—all were economic activities reliant on rain. Deprivation of rain meant deprivation of life and its continuity. The shaman was respected because he was capable of meeting the community’s need for rain. Bringing rain was the primary task the shaman had to perform. After returning from his journey, during which he negotiated with the spirits who control the reins of rain, another task was to pull the rain animal from the Qulta where it lives underwater. The rain animal might be a bull or a cow. After pulling it from the water with a rope, it is dragged over the largest possible area of arid land, then slaughtered and cut up, with its parts placed in the land where rain is desired.

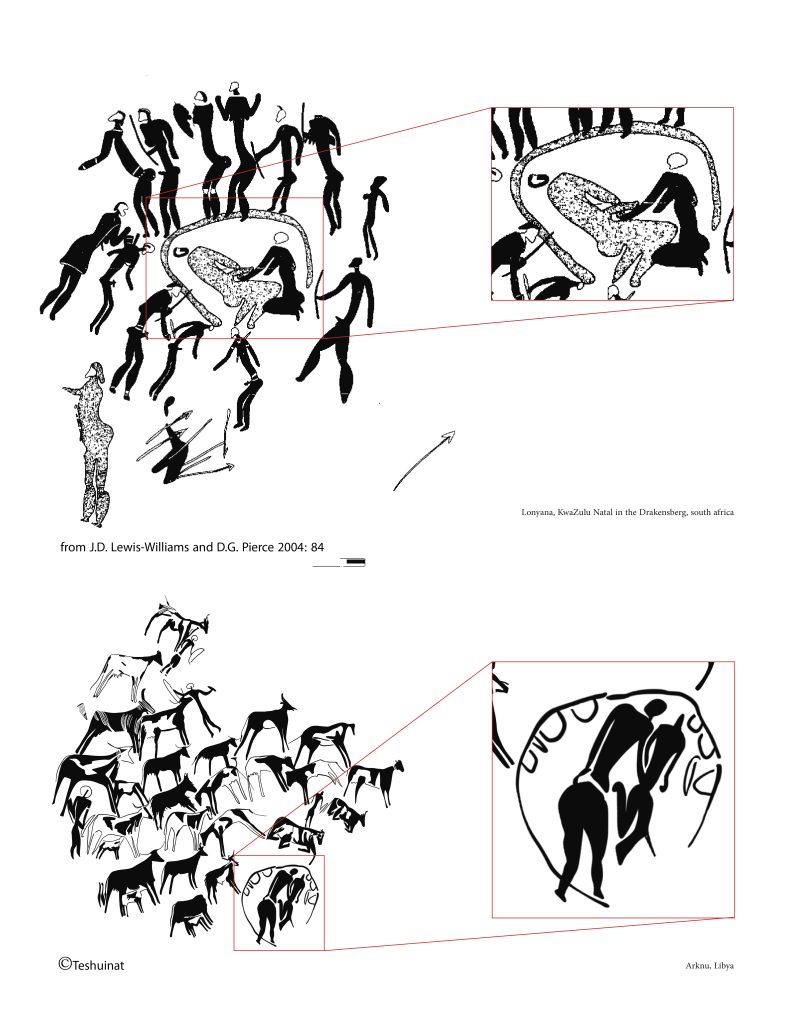

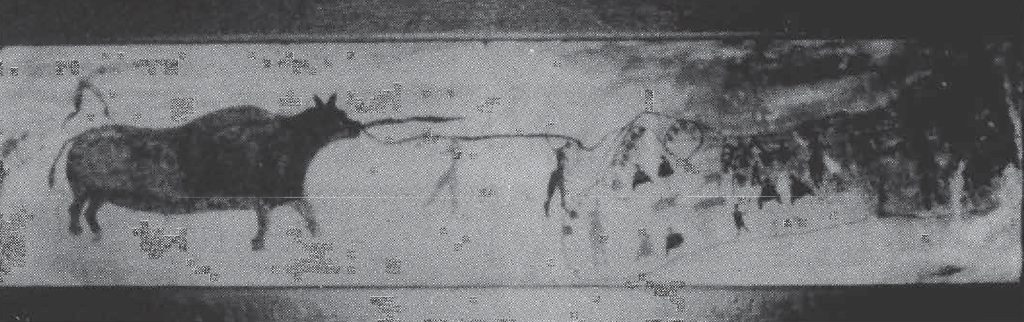

In (Figure 6) from the Jebel Al-Awenat mountains, we see at the top of the scene the process of pulling the rain animal. In a scene from Southern Africa (Figure 7), the image shows the process of pulling the rain animal. Also, there is a scene (Figure 8) from Tassili clearly showing the process of dragging the rain animal across arid lands, tied with a rope, and another scene from Southern Africa representing the same ritual in the same manner (Figure 9).

These are just simple examples of the strange similarities in practices and rituals between Libya and Southern Africa. In Libya, they are perhaps older, as the rituals of the rain religion in Libya are engraved in many places, and these engravings date back to the end of the Pleistocene.

Fig.6 Pulling rain animal from Qulta, Al-Awenat, Libya.

Fig.7 (H.C. WOODHOUSE)

Fig.8 Pulling rain animal, Tin Tazarift, Algeria.

Fig.9 (courtesy of the Rock Art Research Institute, University of the Witwatersrand, the KwaZulu-Natal Museum, and L. Smits; see Smits 1973: 32, fi gure 1)

1-The Archaeology of Shamanism- Edited By Neil Price – Routledge- 2001- p 3-13.

2-SOUTH OF NORTH: SHAMANISM IN AFRICA A Neglected Theme- I.M.LEWIS – Paideuma35, 1989 p 181-188.

Mohammed Altarhuni

Writer and researcher