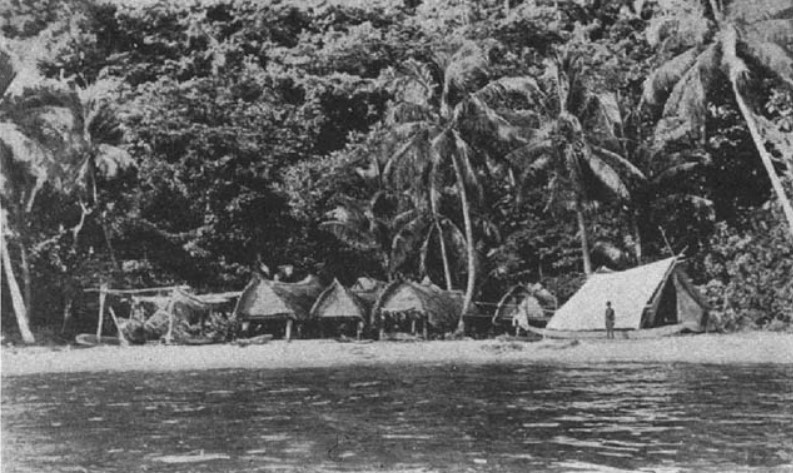

1- New Guinea tent

The Ethnographer’s Dual Places

The Poetics of Disruption

Article: Ethnography, Mohammed Abdallah Al-Trhuni

Ethnographer Gerald D. Berreman writes in his book Hindus of the Himalayas:

“Living conditions in the village were primitive even by local standards, which led me to reject the idea of moving my family there permanently. Except for a period of about four months when I owned an unreliable jeep and could drive along a remote road to within five miles of the village, access from Dehradun was via a nine-mile footpath beyond the end of the bus line, and the final five miles to the village was a mountain trail climbing 2,700 feet. Access from Mussoorie, where my ‘town home’ was located during the last four months, was via a relatively comfortable sixteen-mile trail, though very rugged in places. My home in the village consisted of three small connecting rooms, one of which was continuously occupied by two to four water buffalo. All the rooms were inferior to those inhabited by most villagers. The only food consistently available in the village was grain, milk, sugar, and tea. The water source was a quarter-mile away across a rocky path. In short, Sirkanda was not suitable for long-term family residence by outsiders.”

In the book Tales of the Yanomami: Daily Life in the Venezuelan Forests, Jacques Lizot writes:

“Dawn has not yet broken. The river seems to have stopped flowing; only a few eddies stir the water’s surface. Light wisps of mist float slowly, almost motionless. Not a breath of air. As morning approaches, the moisture condenses in the dense layers of foliage above: now large, noisy drops fall like constant rain. Here and there, a toucan releases short notes from its monotonous song. The morning cold becomes more severe; the Indians light fires, and sparks fly toward the roof. The sun rising on the horizon will soon illuminate the tops of the tallest trees. The great shelter at Karohi slowly returns to life: voices seek answering voices, children cry, and hammocks swing from the movement of bodies without anyone getting up.”

The ethnographer exits their temporal and spatial boundaries. Research imposes residence in distant places. The researcher moves from one exploration zone to another. In the era of multi-sited ethnography that transforms into an imagined journey, the researcher must navigate within the journey’s scope, filled with conflicting emotions. And when they move from one site to another, they must listen to the words that support the movement—from informants, cavities, rocks, and tree branches. In this research task, what guides the body is the spirituality of research. Everything changes when the researcher reaches their destination, which they consider their fieldwork site. They lose their privacy and the space about which they know everything. However beautiful the place they have reached, it remains pale before the conception of the place they came from. Humans carry their home with them, for which they feel an irrational attraction. Neither Gerald D. Berreman’s home in Sirkanda, nor Jacques Lizot’s great shelter in Karohi, resembles the places they lived in. Residing in another place, another culture, and a radically different lifestyle makes you another person. Home is the intimate image of routine actions. Life lived and experienced at home is not the same as life in a distant shelter or a fieldwork tent.

There is a myth that the concept of fieldwork weaves around itself, making the ethnographer’s work ambiguous, mysterious, and controversial. The secret of fieldwork is forgetting the previous life lived at home to merge into another life that could be called imaginary. This imaginary life is based on the skill of improvisation and infallible intuition. The paradox the ethnographer lives is attempting to coexist with a new chaos, not the chaos of the home they live in their homeland. They are required to adapt to relinquishing the idea that home is a place for rest, recreation, and isolation. Certainly, living with four water buffalo is not the kind of life Gerald D. Berreman knows, nor is life in the great shelter at Karohi the kind of place where Jacques Lizot feels isolation.

The ethnographer deals with the mismatch between their text and what happened in the field, the mismatch between the ethnographic life experience and the life we live at home, and the mismatch between the field moment and the moment of writing reports. Bronisław Malinowski says:

“The main field of research was in one region, the Trobriand Islands. Yet, I studied this region with meticulous precision. I lived in that archipelago for about two years during three expeditions to New Guinea, through which I naturally acquired comprehensive knowledge of the language. I carried out my work entirely alone, residing most of the time in the villages. Thus, the natives’ daily life was constantly before me, while incidental and dramatic events—deaths, quarrels, village disputes, public and ceremonial events—could not escape my notice.”[1]

Malinowski lived these periods in New Guinea in a tent (Figure 1). This tent is not a residence; it is a temporary spot on a shore that might disappear at any moment. The difficulty does not end there. Alpa Shah says about the concept of participant observation: “It is a long-term, intimate engagement with a group of people who were previously strangers to us, with the aim of knowing them.”[2] Transitioning to live in another place, from village to village, with a group you have not known before, represents a change in the daily life at home. This requires the ethnographer to reinvent themselves every morning and adapt to an unfamiliar daily interaction. Every discomfort, every pang of homesickness is considered a weakness and a disgrace for the ethnographer. Therefore, they are obliged not to appear as a fragile human, incapable of withstanding the challenges of fieldwork—even if the ethnographer belongs to the same social fabric, they are far from home. And this distance they travel to reach the field stands in the way of fully immersing themselves in its various sites.

[1] ARGONAUTS OF THE WESTERN PACIFIC-BRONISLAW MALINOWSKI- Taylor & Francis-e-Library-2005- p xii.

[2] ETHNOGRAPHY BEYOND METHOD: The Importance of an Ethnographic Sensibility-Carole McGranahan-sites: new series · vol 15 no 1 · 2018- p 5.

Mohammed Abdallah AlThrhuni

writer and researcher