Illustration made by artist shefa salem

Libyan tribes: Between Ethnography and Literary Narrative

Article: Ethnograghy, Hamza alfallah

According to Detienne, the domain of myth lies on the frontier of memory and forgetting. This sensitive, scandal-loving domain is not gratuitous, as he says; it “summons all the specters of otherness. The primitive, the inferior races, the peoples of nature, the language of origins, the wild, childhood, and madness: all are zones of exile, isolated horizons, images of exclusion. And yet, in the face of all these divisions, mythology moves, changes its form and content: it is the irrational that religion confronts, the unreason that reason gives to itself, the savage as the other face of the civilized. It is the absent, or the accomplished, or forgotten stupidity.”[1]

This domain—the domain of myth—is always linked to the journey as a space for conceptions, imagination, and exploration of the Other, a practice belonging to an established knowledge discourse. This Other, the pivotal partner in this symbolic discourse, represents the different system of values. This partner is the partner of cultural conflict, untamed nature, and opposing gods. Because this conflict is subject to an essentially ethnocentric[2] principle, it always works to reveal the tendencies of the outsider and explain them first, not the original nature of this Other emerging from the earth.

In the fifth century BC, Herodotus’s journey to Libya represented the engine of myth-making and the knowledge production of a distant geographical space that necessarily transformed into a marvelous space and an early mythical ethnography about the ancient Libyan tribes: their customs and traditions, their nomadism and social behavior, types of dress and symbols, food, religious rituals, and gods. Although the production of the strange Other inevitably falls into the circle of ethnocentrism, in Herodotus’s text it was more open, and one could even say non-hostile. But how does the Libyan myth transform from the texts of historical and ethnographic journeys into a living myth capable of being rewritten through individual experience, literature, and interaction with the land and the Other, while preserving its knowledge and cultural trace?

Herodotus and the Mythical Libyan Ethnography

The journey’s relationship to myth gains its legitimacy by positioning the Self in confrontation with the Other through historical discourse. This confrontation is imposed by the field nature of the ethnographer’s work, which practices observation. Herodotus is one of the most important early models of mythical ethnography, if one may call it that. This Libyan mythical face is not immune to observation, repeated listening, and fictionalization due to interaction.

Herodotus proceeds on his journey after an intermittent march of ten days between salt hills surrounded by water and people gathering around them, called the “Atarantes.” He approaches his informant, who does not grant him much time to think or contemplate this immense human gathering, telling him:

“These people have no personal names, but calling them Atarantes is enough to address them. We must be cautious, for they may not be in a good mood in this hot weather, because they all curse the sun and hurl the foulest insults at it, for when it shines, it burns them and scorches their land.”

One could say this passage is fit to be placed in the context of a historical novel; it is based on the legitimacy of the historical document about this tribe according to Herodotus, who wrote about these people after crossing the lands of the Garamantes. The salt hills, which he noted in abundance in that region, form part of the same context. He comes and tells us about a mountain hill called Atlas, inhabited by a people called the “Atlantes.” This mountain is not devoid of a mythical dimension according to the environment and natural landscape, due to its connection to the sky like a massive, towering pillar, as the locals tell him about it and its strange inhabitants and their bizarre customs:

“They eat no living creature, and see no dreams in their sleep.”[3]

These poetic lines, pulsating with the literary quality of the anxious, documentation-obsessed ethnographer, do not give him sufficient opportunity for the objectivity we call for today to distance suspicions from what he writes. Rather, he flows with the dream of finally finding the strangeness for which he embarked on a long journey. This departure was like reaching the impossible text, for this text is the text of Barthesian pleasure and the joy of addressing that hidden region in our minds that Detienne speaks of—the region of fear and the bewildering magic of a primitive world that nostalgia drives us to create whenever we reread history.

Illustration made by artist shefa salem

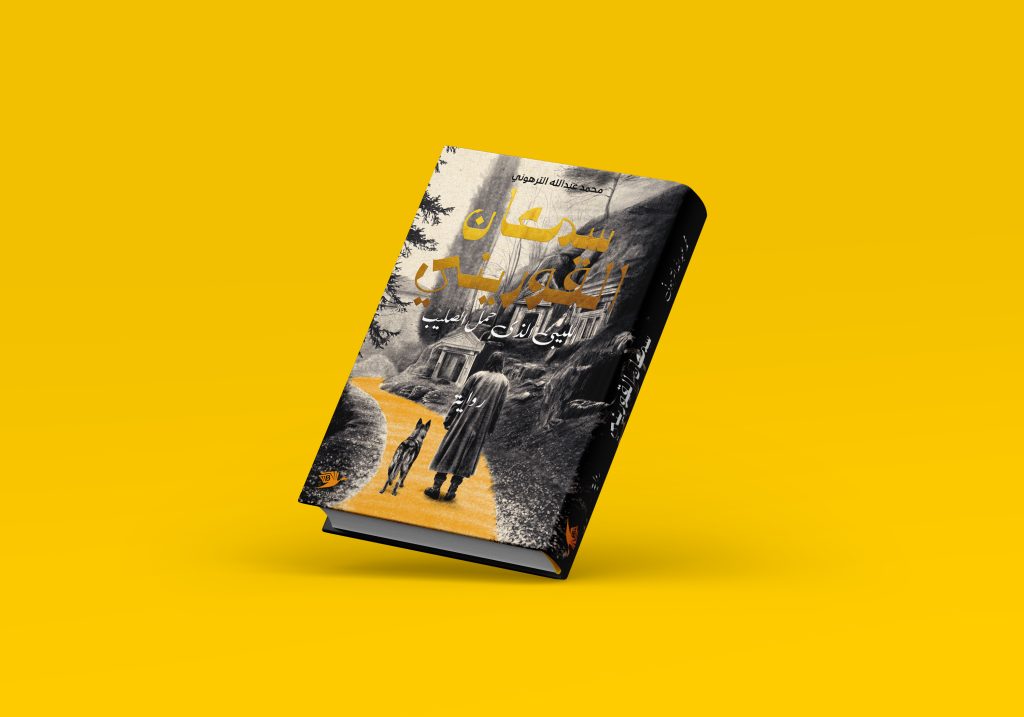

The Libyan Who Carried the Cross

Within the same ethnographic context, we find the novel “Simon of Cyrene, the Libyan Who Carried the Cross” by writer Mohamed Abdullah Altrhouni, where the Libyan myth does not separate from the journey within it, nor does ethnography, during the adventure of Battus on the island of Platea, what is now called Gulf of Bomba:

“Battus was ready for this journey, and Pythia had given him the goal on which he must focus. When he arrived at the meeting place on the island, he waited in the boat with the men because he felt Minya might appear at any moment. Finally, Minya appeared with some men. Everyone in the boat was shocked, for those with Minya had white skin with golden blond hair reaching their shoulders and pointed beards. This image before them had never crossed their minds. The bodies of the Libyans showed their great strength. The men wore long leather robes, a loincloth, and an animal’s tail dangling from a belt that cinched what they wore to their tattooed bodies covered with many letters and marks, feathers on their heads shining under the sun, and leather shoes protecting their feet.”[4]

While writing this work, Altrhouni set out with a small travel bag on a long journey for months alone to eastern Libya and stayed in the city of Shahat to write. In this ethnographic excerpt from his novel about the members of the Tehenu tribe and their culture, we find a journey within the journey that breaks out of the circle of ethnocentrism in the ancient Greek discourse, to establish the discourse of the perpetually absent Other so that the men of the Tehenu can speak of themselves and their identity when receiving Battus.

There, in the city of Shahat, Altrhouni’s narrating self, surrounded by myths in his isolation, prevails over the tongue of the Libyan heroes of his novel, especially Bushiasha, to save them from absence. The journey narrative takes on its mythical dimension as a structural condition for inventing a Libyan myth in direct contact with the land. Bushiasha sits on a rock and narrates his own personal journey with Libyan Cyrene; he does not look at Battus as merely an outsider driven by the prophecy of foundation, but at the journey as part of his own myth as a founder of consciousness, and the child Buzid’s discovery of him and his role in order to found the future of his own journey. Here, myth is not born from ignorance but through its elements in the natural landscape of the island and the natural scene of its inhabitants, and its symbolic geographical space, which is formulated within the system of meaning specific to Bushiasha’s emotional and contemplative relationship with his country’s history. This relationship does not merely convey historical facts but extends to reshaping them through the journey, so that our myth gains a knowledge and cultural trace.

The nostalgia in the heart of Bushiasha, the hero of this novel who knows only caves, mysterious forests, sorcerers who steal treasures buried in tombs, the crimes of colonialism and war, and the heads of statues showing a half-sad gaze of clay under his feet—as he tells the child Buzid while walking in the valleys about the meaning of having a mythic existence by immersing oneself long in the details of the marginal time of fulfilled prophecies, unheard prayers, and the final calls of death in the caves—this existence whose interaction is only realized by narrating the journey and the intimate personal conflicts it entails with what we might call the repression of memory that does not speak of itself or reshape its stations based on the voice of the poetic dreamer who feels compelled to tell his tales to others. And that is why the child Buzid was found, to tell his own story in turn to Altrhouni, seated at his writing table between the walls of his room in the lodge with his dog Raad, after leaving Sheikh Buzid, who grew up on the sound of Bushiasha’s voice echoing ceaselessly in both their dreams throughout the writing period and after its end, saying:

“The world is before you, and this world can easily take shape in the path of the journey because the narrative will give everyone who nourishes their way a door to find joy in the imagination on the tip of our Libyan myth, which we can only rewrite through contemplation.”

[1] مارسيل ديتيان، اختلاق الميثولوجيا، ترجمة د. مصباح صمد، مراجعة د. بسام بركة، الطبعة الأولى، بيروت: المنظمة العربية للترجمة، توزيع مركز دراسات الوحدة العربية، أيلول (سبتمبر) 2008.

[2] James Redfield, “Herodotus the Tourist,” Classical Philology 80, no. 2 (April 1985): 97–118, accessed August 17, 2013, http://www.jstor.org/stable/270156.

[3] هيرودوتس، أحاديث هيرودوت (487/489-425 ق.م) عن الليبيين الأمازيغ، ترجم د. مصطفى أعشي، منشورات المعهد الملكي للثقافة الأمازيغية (مركز الدراسات التاريخية والبيئية)، الرباط، المغرب، د.ن، 2008.

[4] محمد عبدالله الترهوني، سمعان القوريني (الليبي الذي حمل الصليب)، الطبعة الأولى 2021، الطبعة الثانية 2025، طرابلس، ليبيا: مكتبة طرابلس العالمية للنشر والتوزيع.

Hamza alfallah

Writer and researcher