What Remains for the Ethnographer?

Article: Anthropology | Hamza Alfallah, 2026

In all our childhoods, an attachment to comic magazines featuring superheroes was pivotal for opening channels of imagination and adventure. It wasn’t just flying, or bending and breaking steel gates, or lifting heavy trucks that were the most prominent traits of these characters’ powers. These abilities extended to mental control, reading thoughts, and even invisibility to accomplish arduous rescue missions. In my childhood, all these stories about these saviors were a source of physical imitation—jumping and climbing, to designing colorful paper masks and long capes in the style of Superman, culminating in inventing stories and mimicking voices. These spectacles of rescuers maintained a high influence in creating imaginary worlds throughout playtime.

But what is the connection between this solitary world and the lives ethnographers live on their journeys? One could say that the ethnographer is a superhero with exceptional mental abilities linked to willpower—a hero who resists the idea of death from trivial causes, battles harsh climatic conditions, tests the mood of the most hostile nature, and easily enters for long periods into the circle of mythical absence for months in the wilderness or beyond high sand dunes in deserts, crossing vast distances in different environments, searching in remote wildernesses for diverse cultures. They can adapt to the strangest customs and foods, switch their tongue, and completely forget where they came from to reach their naked primitivity in the jungles. But was the ethnographer ever truly a superhero according to this conception?

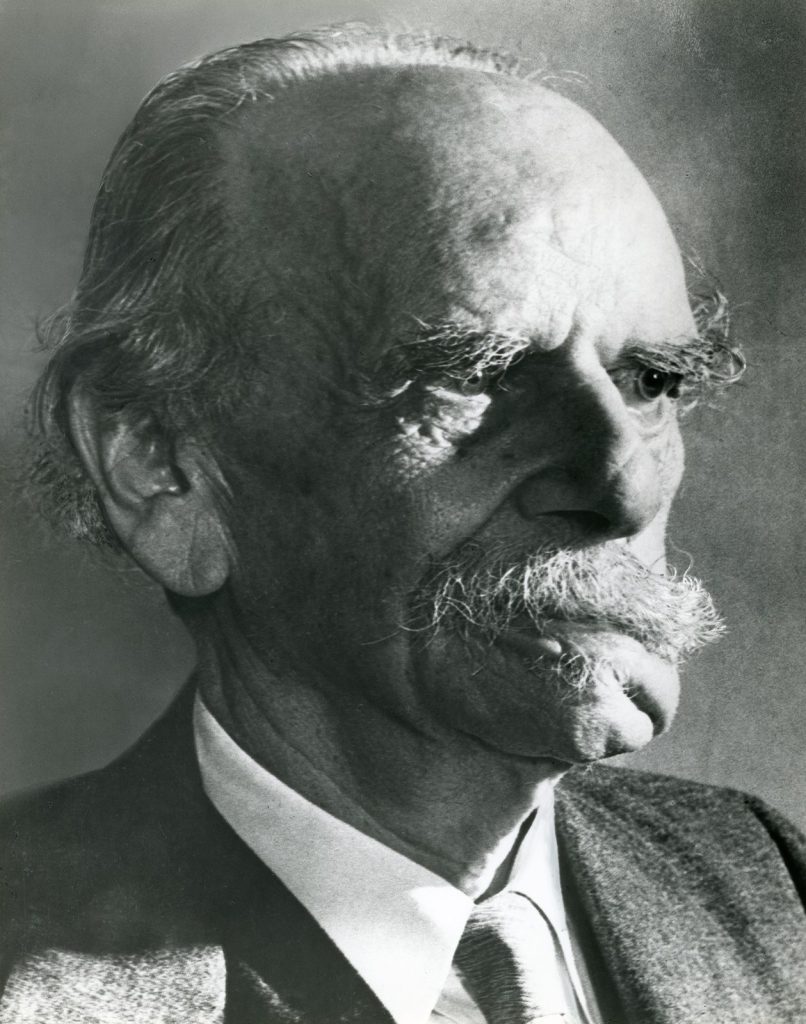

On Baffin Island (1883–1884), the anthropologist Franz Boas spent a year in the hell of an extremely cold polar environment in Cumberland Sound, suffering from food shortages and the psychological pains resulting from prolonged isolation, attempts to adapt to learning a difficult language without dictionaries, and communicating without an intermediary with the indigenous people amidst a network of mobile kinship groups. Boas had sailed from Germany to that island on one of his first trips to the Arctic, driven by the curiosity of exploration and fieldwork. Boas, the emerging anthropologist, fascinated by the flexibility of nomadic life, did not lose the poetics of contemplating shelter through the eyes of its inhabitants, like a moving body addressing the ecological mind of peoples who do not know settlement. He would observe the ceiling of his snow dwelling—the igloo—from his elevated sleeping platform, occasionally glancing toward a light growing from the burning of seal oil emitted from an oil lamp. The wind outside had a very sad and dry sound, reminding him of the necessity to reconsider all European preconceptions about the Other, and the engineering intelligence of the primitive mind that built a dwelling with effective thermal insulation from blocks of packed snow.

Boas rises from his sleeping platform and walks slowly toward the entrance, driven by astonishment at a group of Inuit coming from afar, laughing loudly in the face of death. He wonders, almost in panic and madness, about the possibility of easily breaking into laughter while narrating painful tales in a composed manner about hunger and being lost—how can one, in a charming and emotional way, stand smiling and alone on the edge of the unknown?

He steps back, contemplating carefully his ability to continue living and repeatedly listening to mouths molded with songs, lullabies, and myths, in order to capture more facts, silent gestures, bodily movements, and an admirable wandering gaze into the gloomy horizon. Near a thick notebook, he sharpens a pencil with a small knife for immediate writing to record his turbulent feelings: “I live among people whose language I barely understand, under conditions testing the limits of human endurance.” He puts the pencil down—his scribbling arouses more anxiety and insomnia before sleep, preventing him from connecting with the spirit of the frozen earth. He returns to lying on the platform, trying to close his eyes against a frighteningly vast whiteness, to hear the cracking of ice in a state akin to fainting:

The natural scene moves quickly, imaginatively, like a stubborn flower in drought, all the colors of its space at once, like a painting of cold metallic blue and milky grey, from the fading boundaries between sky and snow. Fog rises from the water like a huge pack of wolves, and suddenly the fierce smoke retreats backward without prior warning, as soon as he opens his eyes.

There, Boas finds himself far from the forms of Western rationality and its tendencies to dominate nature, realizing he had been a prisoner of his previous illusions about it, to feel more familiarity in his intimate ice hut than before. At that pivotal moment in the history of the fieldwork experience, the silence of those huddled in their dwellings rises, remembering the dense calm in the eyes of one of the women who were warmly sewing protective clothing for the tribe’s men when he first landed ashore in the summer of 1883.

ooking at Boas’s fieldwork experience on Baffin Island, I can consider him one of those heroes I spoke of from the comics, alongside Margaret Mead in Samoa and its people, Ruth Benedict with the Pueblo tribes, and Malinowski’s diaries in the Trobriand Islands around 1918. However, looking at the ethnographic experience today raises an important question about the nature of the ethnographer’s work in the age of algorithms—this ethnographer burdened with this enormous load of the sufferings of those heroes and the various theoretical models they developed through all those experiences.

While ethnography once relied on producing meaning according to the social context by activating tools of knowledge, investigation, and daily immersion with studied communities, we find it is not immune to the transformations brought about by technology today. Can the digital platform become the direct field of work, and can the ethnographer’s function, centered on the meaning of the journey to discover the unique and marginal within it, be replaced?

On social media platforms, an interesting phenomenon is observed: the fever of rapid documentation of different cultures worldwide, by showcasing the daily lives of many tribes in Africa, for example, in the form of short reels not exceeding perhaps fifteen seconds. This phenomenon invites me to reflect on how the lives of these people have been reduced and transformed into mere digital inputs, far from understanding and interpretation. This does not mean advocating for the monopolization of representation by the ethnographer as a mediator between culture and the world, but rather concerns the value of this type of representation shown to us by phone screens. Through this screen, these groups have managed to produce their own image. However, this image suffers from a lack of meaning and is marred by many flaws, and cannot by any means be considered entirely innocent, due to its ability to manipulate what it wishes to show and hide. This transmission represents the fading of narrative authority from within the fieldwork experience and its monopolization for the benefit of the platform, not for the observing ethnographer, who has necessarily become one of many voices in an open space.

Recently, for a period of time, I followed a series of short, fast-paced reels that I mentioned, about the Hadzabe tribes, one of the groups living in northern Tanzania, near Lake Eyasi in the African Rift Valley. These groups publish their daily lives continuously and intensively, resembling entertainment content. Yet this directed content made me feel anxious just watching it, due to the comments that have become mechanisms for issuing judgments, amid the absence of social control standards in virtual space, in addition to submission to the logic of likes, repeated views, and exaggerated performance to provoke the audience. By this logic, we are facing a culture being reformulated to be watched, not to be lived and closely observed. So, what is the ethnographer-follower behind their screen to do, given the disappearance of the classic isolation of their work as an epistemological condition, before a high-quality technological connection that might expose these groups to losing some of their authenticity, and impose a new awareness of self and the gaze of the Other, and their ability to reproduce their cultural difference according to the terms of the digital market?

These platforms present themselves, not the culture of the group; individual performance, not shared fieldwork. This presentation is linked to a kind of algorithmic industry of content from incomplete ideas, whose assumed deficiency raises ethical questions in this field related to falsifying the spontaneity of these groups’ interaction, and digital control over spontaneity for the voluntary response to market demands, in order to turn this type of provocative practice into a visible commercial commodity.

It is entertaining to watch carefully selected customs of a human capable of hunting a small crocodile to grill it, or speaking in a different and funny language to others, relying on bird sounds to economically benefit from this representation. But do these short clips truly satisfy the community’s needs and its cultural representation, and the audience’s need for more understanding and interpretation, not just enjoyable views within a digital structure that its owners cannot possess?

Even if they have become vocal and able to freely express themselves away from the illusions of Western centrality as a knowing subject, and even if this expression is sincere, can we say that these societies have invested in this transformation to finally rid themselves, via these smart media, of the voice of the Other’s ideas that do not understand them and impressions about them? Or have they become more subjugated to consumption, and been drawn in to satisfy the desires of anonymous visitors, perhaps under the pretext of documentation for entertainment?

I had posed my question as the title of this short article: What Remains for the Ethnographer? Returning to the fieldwork experiences of Franz Boas and others, we can say that ethnography is not as much threatened as it is in a state of constant change, and has perhaps become more complex than before, in a less understanding age, where human experience has turned into mere performance, difference into a visual marker, and daily life into a superficial narrative. This narrative is subject to the logic of virality versus contextual understanding, close immersion, daily participation, listening, and the search for authenticity.