Some Similarities Between Rock Art in Libya and South Africa

Article: shamanism | Mohammed altrhuni, 2026

Researchers have a sense that there is a connection between rock art murals everywhere in the world. However, these similarities found in rock art, which support the hypothesis of a universal connection, do not present themselves easily. Some scholars believe there are potential influences from one region to another. Others say that similarities exist, but there is no comprehensive correspondence by any means.

Nevertheless, certain pictorial expressions use the same style in regions very distant from each other; indeed, some murals are almost identical at times. Is this correspondence in pictorial expression a result of cultural influence? Is the basis of this correspondence a unified prehistoric religion? Do these similar works represent a long-lasting and deeply historical expressive tradition?

We face questions that cannot be answered easily, nor discussed with absolute certainty. We also do not claim that there was a single prehistoric culture that led to a series of similarities in rock art, but one could argue that there was a single prehistoric religion that led to similar pictorial expressions of its rituals. As an example, there are similarities that sometimes reach the point of correspondence between the rock art of Libya and South Africa. Here, I will present some examples that support our viewpoint on the subject.

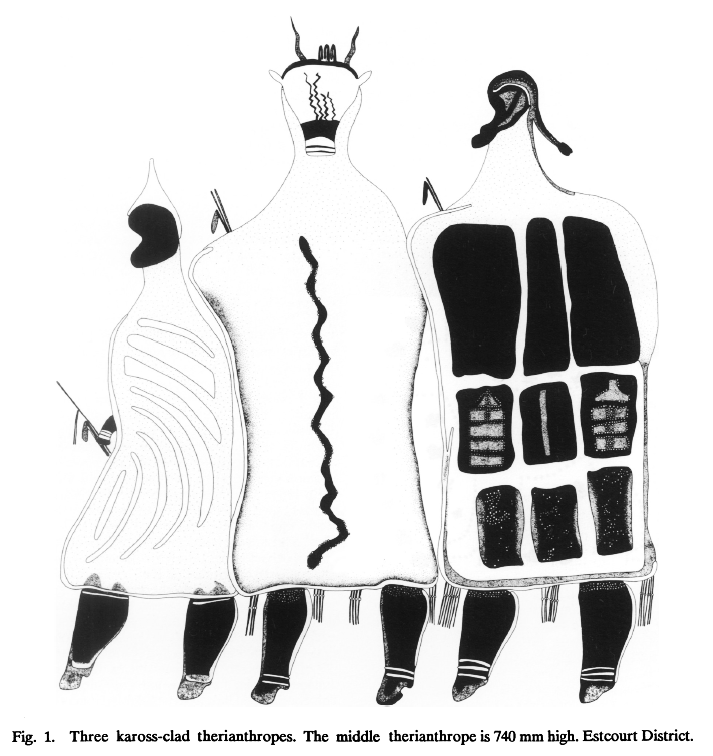

In an article by archaeologist Thomas A. Dowson titled “Dots and Dashes: Decoding the Internal Visions in Bushman Rock Art,” we find in Figure 1 a caption under the painting: Three figures in animal form, wearing garments that cover the entire body. According to Dowson, these figures are hybrid beings between human and animal, not fully human. This blend of human and animal traits is interpreted within the framework of Bushman beliefs concerning trance or ecstatic experiences. The shaman, when communicating with the spirit world, undergoes a transformation into the animal whose supernatural power they harness. These hybrid beings are the result of an altered state of consciousness and often appear against a background of geometric shapes—grids, zigzag lines, and interlocking curves.

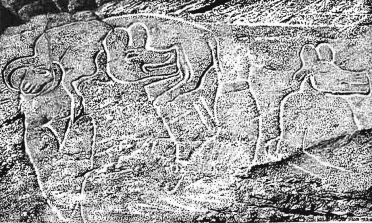

In Figure 2, a painting from Tin Bershula in the Afar region south of the Acacus, we find the same forms as in Figure 1, also resulting from an altered state of consciousness. If we place the figure on the left in Dowson’s article beside the figure on the right in the Tin Bershula painting, we undoubtedly observe a similarity that may border on correspondence. Meanwhile, the figure on the right in Dowson’s painting closely resembles the figure on the left in the Tin Bershula painting. Given the absence of a shamanistic perspective in the interpretation of Libyan rock art, I have found no commentary on these figures. Such similarity raises many questions, the most important being:

-

Was description sufficient to interpret Libyan rock art murals?

-

How can we explain this similarity between the two paintings if we do not acknowledge a primal religion whose traces exist on every continent since the Upper Paleolithic?

-

Is it not time to reconsider previous interpretations of Libyan rock art, employing a poetics of interpretation? Without it, we will not escape the cycle of descriptive discourse that is read as interpretation.

Another example of this similarity between Libyan and South African rock art: In Figure 3 from Matkhandoush (al-Masāk), we are presented with a hybrid human-animal figure. This figure has the head of a jackal and carries on its shoulders a bull that is completely submissive. In Figure 4, also from Matkhandoush, a figure with a jackal’s head carries a bull, smiling and extremely happy. Regarding Figures 3-4, Jean-Louis Le Quellec states in an article titled “Neither Human Nor Animal: The Transformers. Is This Theme Worth Contemplating?”: “Since no human, masked or not, could perform this act, this being is supernatural.”

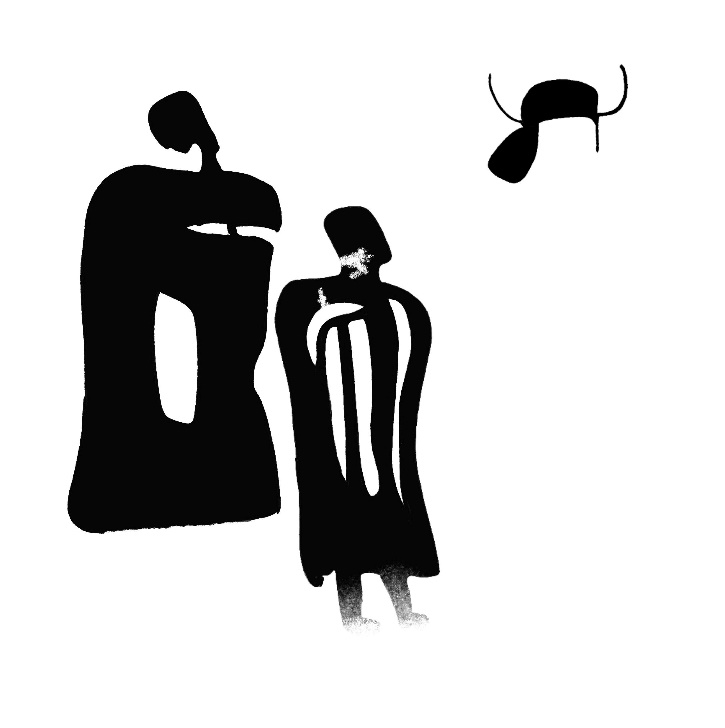

In Wadi Tin Sharuma, there is an image published by F. Pothier showing a jackal carrying a rhinoceros, the latter appearing like a toy in its hands. In Figure 5, we see a figure carrying an eland on its back. Peter Garlake, author of the article “Transforming into Animals in the Rock Art of the San People,” says this figure is in the process of transforming into an eland. Transforming into an animal means controlling the trance state and mastering the animal helper. The moment of transformation into an animal is the moment of acquiring supernatural power. Shamans observed the physical changes of certain animals and viewed this transformation as a kind of power and magic. To attain this power, they invented techniques of altered states of consciousness to reach it.

Undoubtedly, shamanism—through these similarities—represents a global, cross-cultural phenomenon. To study Libyan rock art without taking the shamanistic perspective into account means failing to place it in its correct context, and all interpretations will remain mere description that neither advances nor delays our understanding.