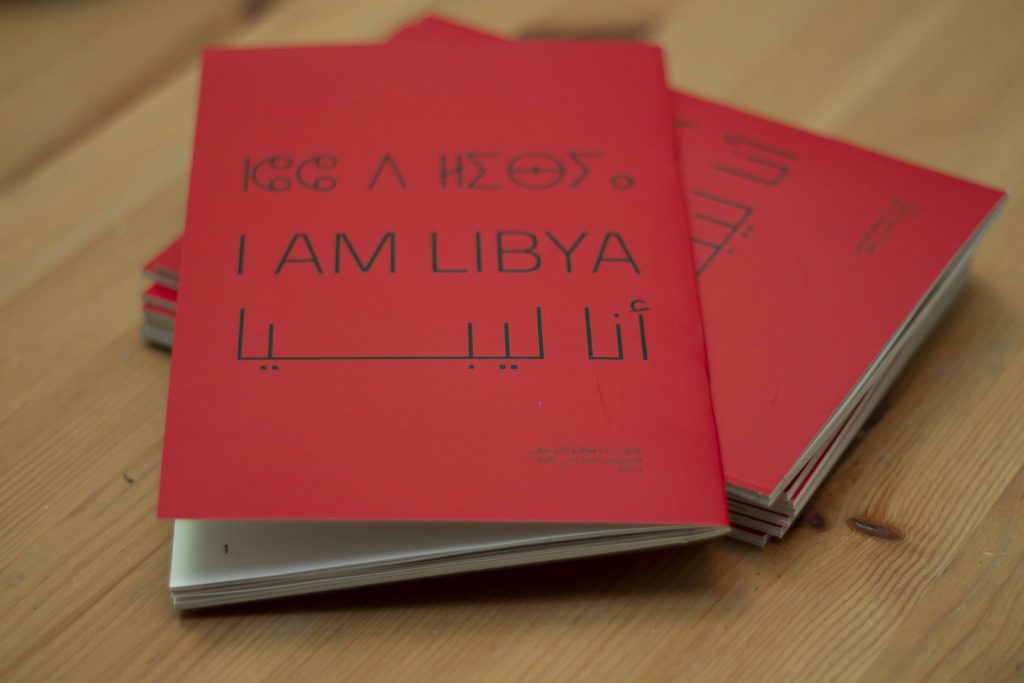

“I’m Libya” Exhibition

On October 27, 2021, the first fine art exhibition was launched as part of our “Identity” project. It was the first solo exhibition for visual artist Shefa Salem and its inaugural edition in the city of Benghazi, titled “I Am Libya” We chose this direct title to encompass several key thematic elements across eight original paintings by the artist, covering a significant cognitive portion of Libyan history.

It begins with the painting “The Libyan flute” presented in a contemporary style, highlighting the importance of this musical instrument as the first known wind instrument, discovered in the Haua Fteah cave—one of the world’s most prominent historical landmarks due to its significance in African archaeological history and modern human prehistory. Located in northeastern Libya, scientists estimate human presence in this cave dates back two hundred thousand years. Through it, the emotional relationship between ancient Libyans and the art of inventing the flute as the first discovered wind instrument of its kind was revealed, justified by the discovery of a portion of a bone flute during excavations in the cave in 1955.

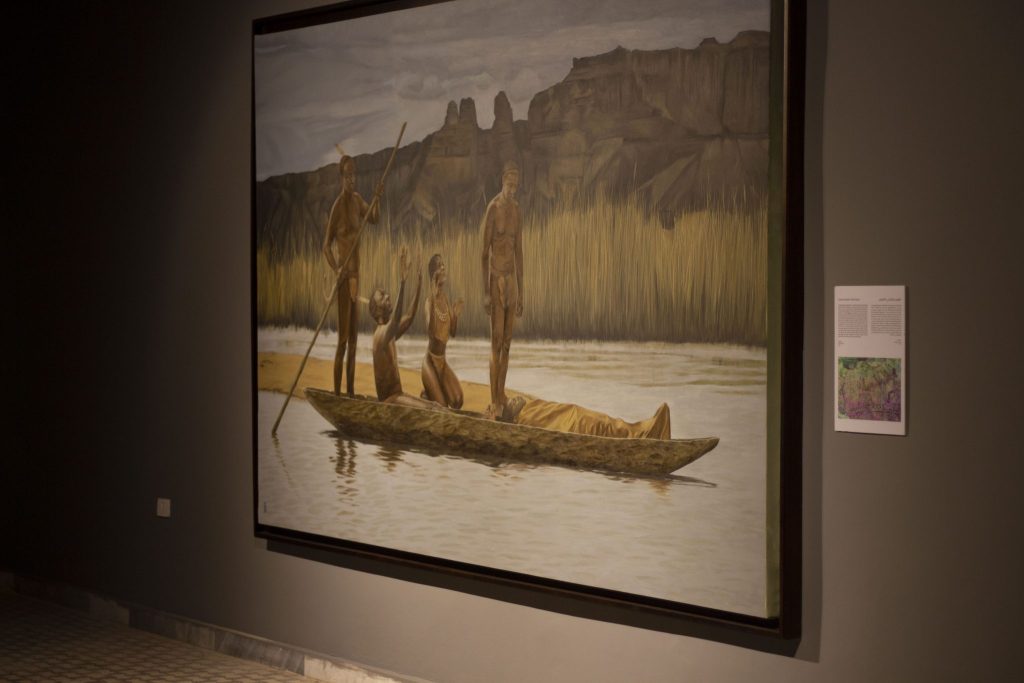

The second work is “Funeral Rituals in the Acacus.” This piece carries an inspired, poetic tone, where grief becomes a living memory expressing the rituals of ancient Libyans in preparing the deceased’s passage to the other world. In the ethnography of ancient Libyan tribes, this passage has a long tradition that varies according to their views on life and death, expressing connection with their ancestors to draw inspiration for dreams and prophecies.

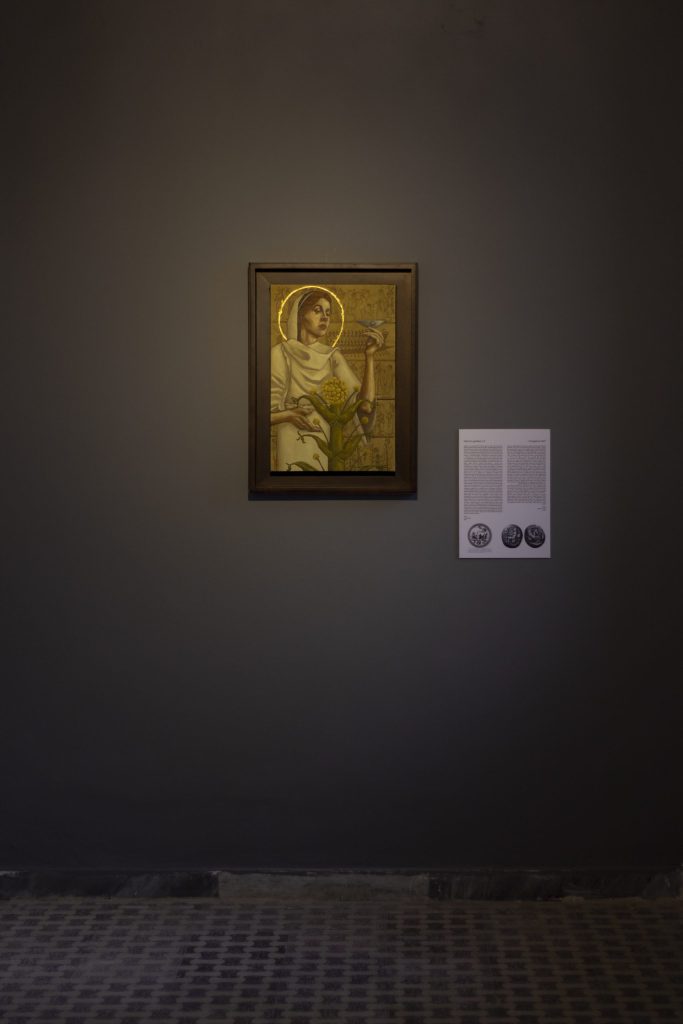

The third painting is “Silphium goddess” For Libyans, this mythical plant was the treasure of ancient Libya, which disappeared in the first century AD due to overharvesting. In this painting, the expression is not limited to the plant as an economic wealth in itself but gathers all factors of its absence in the gaze of the two women representing the work—a look of perpetual nostalgia for this intimate Libyan magic in its sturdy stems and rough leaves.

As for the fourth work, “Libyan family of Tehenu” in Their Leather Garments, whom Herodotus described as “Crimson” (a bluish-red color) as one of the distinguishing marks that set them apart. This family, particularly in this painting, has eyes filled with determination to resist death and drought. They inhabited the western oases after migrating from their original homeland in the southwest—the Tassili and Acacus mountains—carrying with them their ancient religion, culture, and water myths engraved by their dreamer ancestors, who etched the promise of rain onto desert rocks.

The fifth painting, “Sahara chariot – the garamants” comes within the same symbolic context of Libyan desert culture. Emphasizing the strength of this civilization, artist Shefa Salem places the chariot before the viewer to travel with them across rugged paths, guided by the hands of the knight driving it from Wadi al-Ajal to the dream of the enduring influence of the Garamantes and the depth of their economic and military dominance into the heart of the Sahara. This painting is one of ancient Roman anxiety—the fall of generals and the failure to subjugate Libyan lands.

The Libyan flute

Funeral Rituals in the Acacus

Silphium goddess

Libyan family of Tehenu

Sahara chariot – the garamants

The Night of the Nine Bows

The Kaska Dance

Silphium goddess